American Zionism and the Silencing of Palestine

Part 2: Inventing the Past to Justify the Present

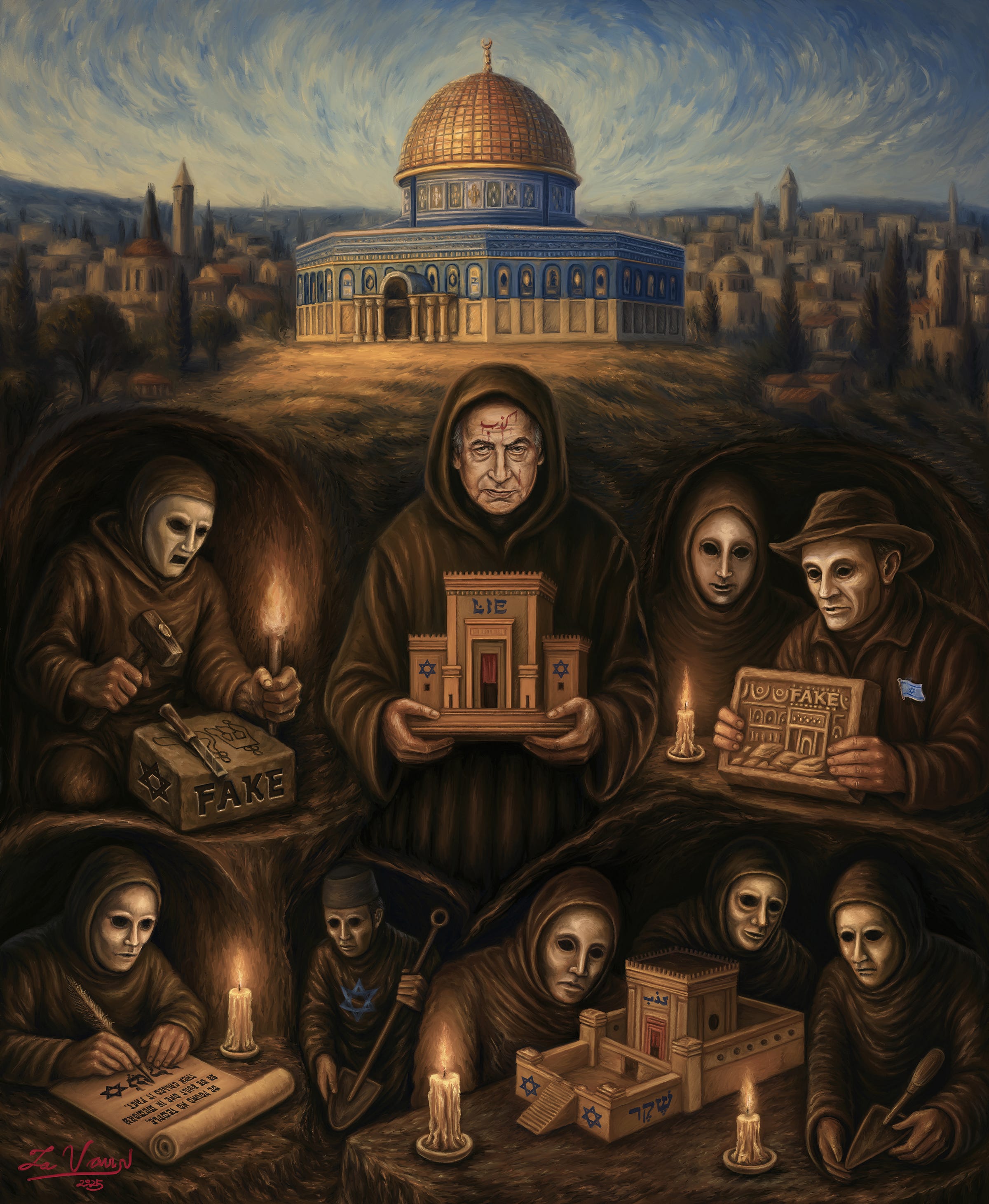

“Most of those in the fields of the Bible, archaeology, and Jewish history—who once searched for evidence to confirm the biblical story—now agree that the emergence of the Jewish people was radically different. These facts have been known for years, but Israel is a stubborn nation that does not want to hear about it.”

— Israeli archaeologist Ze’ev Herzog, Tel Aviv University

For decades, the story of Palestine has been buried beneath myth, distortion, and Orwellian inversions of reality.

Western discourse begins with an unquestioned premise: Israel's "right to exist" as a state is sacred, its "right to defend itself" absolute. Palestinian dispossession is either denied outright, rendered invisible, or reframed as merely correcting an "ancient injustice." Their self-determination is treated as conditional, perpetually negotiable, or simply ignored.

Somewhere along the way, the supposed right to the creation of a Jewish state came to justify the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.

But strip away the rhetoric and any alleged "right" that necessitates the violation of another's rights is no right at all. Even less so when it precariously perches on decades of lies, fabrications, and forgery.

Part 1 examined how American Zionism's messianic foundations have driven U.S. support for settler-colonialism in Palestine, shaping war, occupation, and foreign policy. Now we confront the historical fabrications that rationalize that support: the deliberate invention of a mythical past to normalize a violent present.

This is not "complicated." It is settler-colonialism. And it must be called what it is.

So When Did This Really Begin?

Some claim it's a "conflict" that's been raging for thousands of years—an ethnic dispute between ancient enemies over the same land. Others point to October 7, 2023—saying there was peace until Hamas started the war that day. One narrative clings to the moral laziness of "two sides" and the fantasy of "just wanting peace." The other erases history altogether, absolving Israel and its imperialist backers of every settler-colonial crime that led to that day: oppression, subjugation, occupation, dispossession, apartheid, ethnic cleansing, and genocide.

To answer this question requires us to trace our way backward through history.

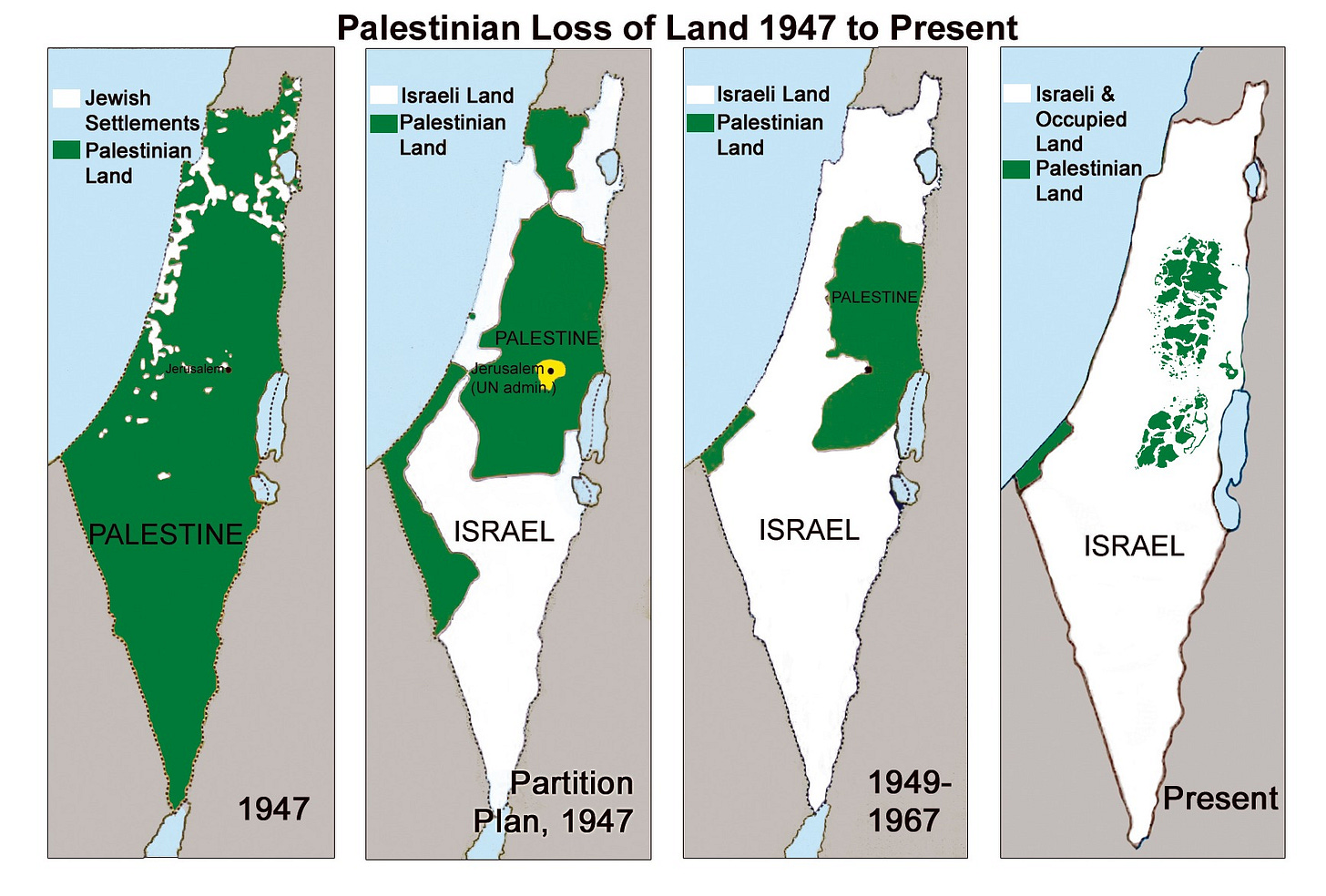

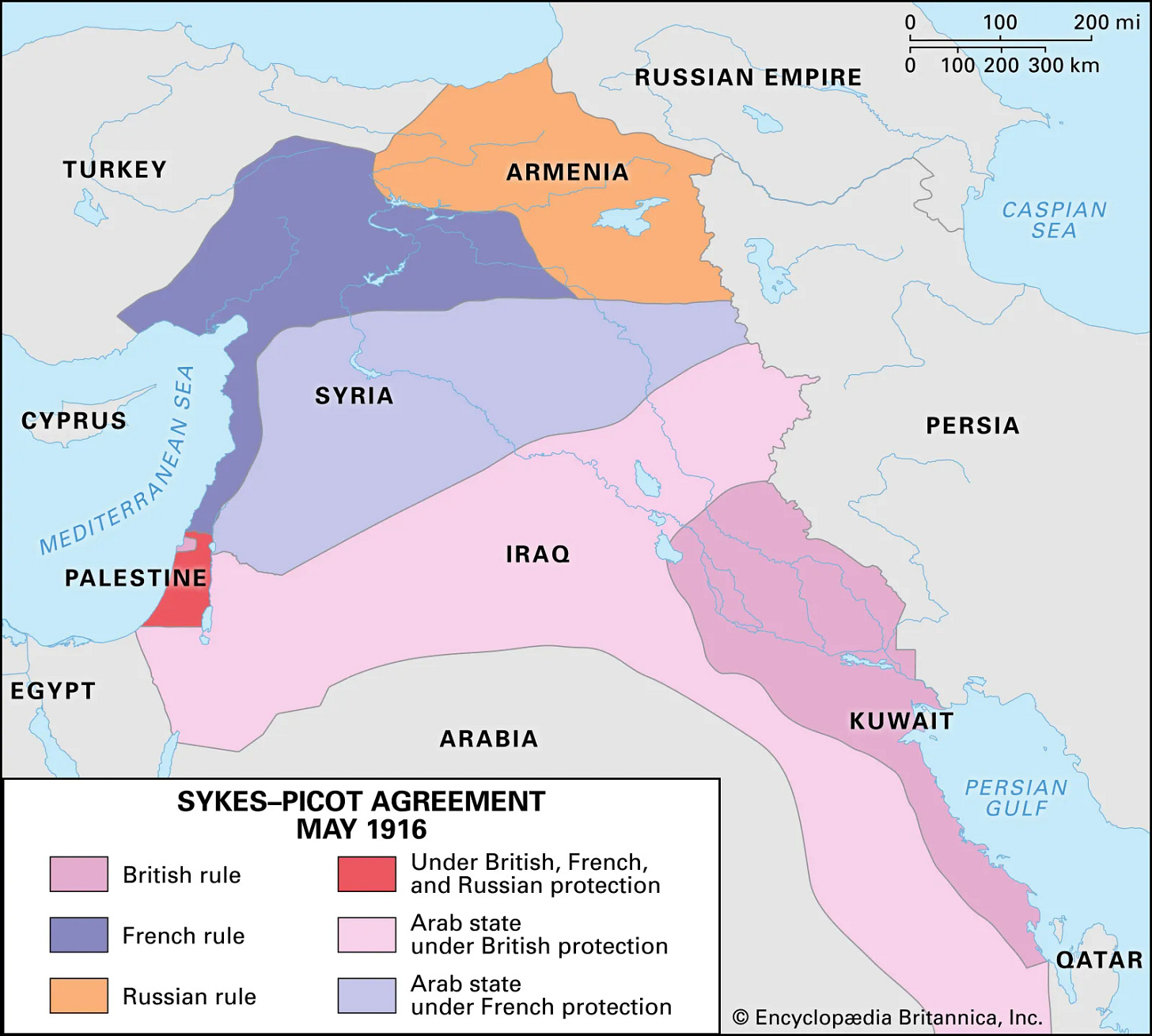

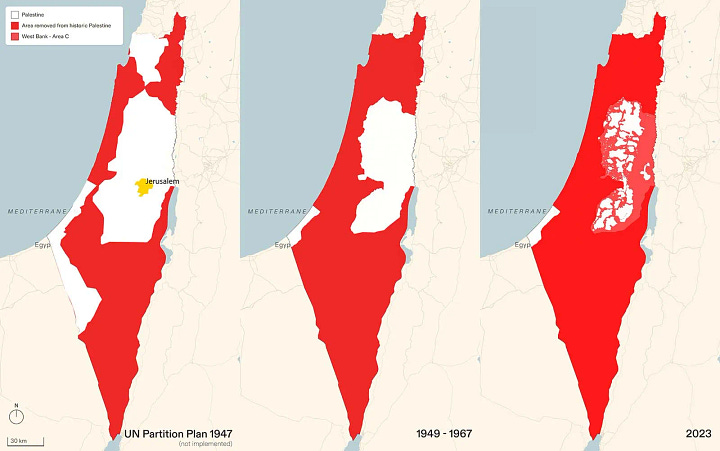

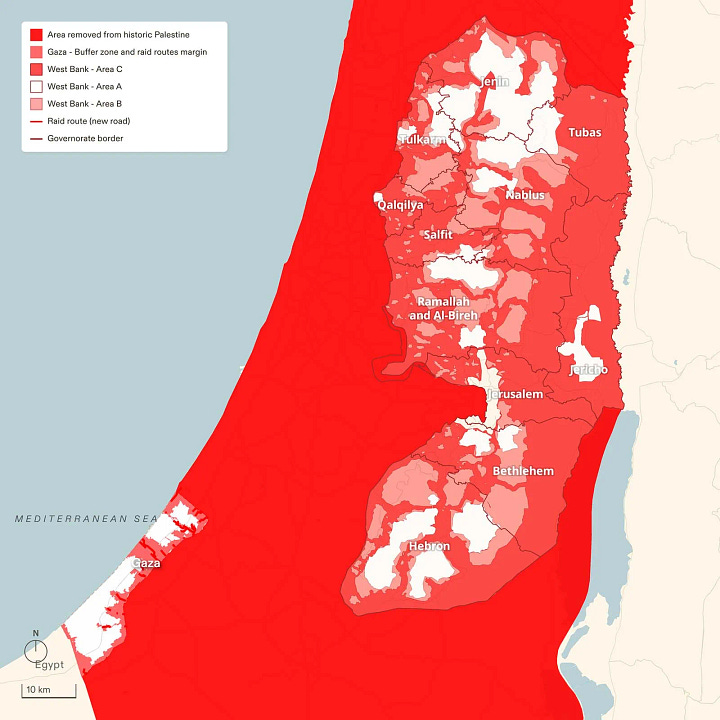

We don't need to go back thousands of years—just a few generations. The Nakba of 1948 wasn't the starting point, but it created this ongoing reality. Since then, it has taken the form we recognize today: a settler-colonial regime imposed by the Israeli military apparatus and sustained by American imperial power—a direct transfer of colonial control from British imperialism to American dominance. The Nakba itself emerged as the inevitable consequence of the 1947 UN partition plan.

In the wake of the Second World War, Washington engineered a global order built on institutions it could shape, control, and leverage. The Marshall Plan was launched to reconstruct Europe under the banner of rebuilding and cooperation—a program that opened European markets to U.S. businesses and influence, securing economic dominance for the rising superpower.

The Bretton Woods system—anchored in Washington by the IMF and World Bank—was created to establish long-term economic hegemony; NATO to extend a military shield across the Atlantic; and the United Nations, headquartered in New York, to legitimize Western authority on the global stage. While these organizations had different purposes, they all strengthened the position of the U.S. as the central global power.

The global economy was tied to the dollar—first made the reserve currency through Bretton Woods, and later reinforced through oil trade payments (the petrodollar system)—while international security rested on Pentagon military strength. Countries that joined this system had to accept U.S. strategic interests and leadership.

The UN stood at the heart of this architecture, offering institutional legitimacy to a Washington-centered world order. Through it, the U.S. embedded diplomacy in a framework it helped design and still controls. This created a forum where imperial agendas were exercised multilaterally, where Western ambitions were presented as global consensus, and where hegemonic power gained the appearance of legal authority. This institutional infrastructure allowed the U.S. to shape the post-war world in its image, projecting power without the need for formal empire.

UN Resolution 181, passed in 1947 by the newly formed General Assembly (just two years after the UN's creation), called for dividing Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem under international control. This plan ignored the actual situation: British Mandate records and UN documents showed that Jews owned only 7% of the land, yet they received 56% under the plan. Palestinians naturally rejected this unfair arrangement.

In response, Zionist forces launched armed campaigns of expulsion and destruction across Palestinian-majority areas, guided by Plan Dalet—a documented Zionist military blueprint for systematically depopulating villages and securing territory by force—using the same settler-colonial tactics still deployed today.

The Partition Plan was a fraud from the start. Its backers knew the Zionists supported it only as a tactical move to secure statehood—intending all along to discard its constraints on territory, governance, and international oversight. Truman's administration pushed it through, lobbying smaller countries to vote in favor by applying political pressure and promising aid, all while well aware of Zionist intentions.

As David Ben-Gurion, the founding father of Israel and its first Prime Minister, put it in 1937, referring to the earlier British Peel Commission proposal, "We accept the partition plan, but the boundaries of the Zionist state will not be fixed and final." A decade later, on the eve of statehood, he was even clearer, stating, "The acceptance of partition does not commit us to renounce Transjordan, this is only a stage in the realization of Zionism."

Partition was never meant to be a permanent solution. For Zionist leaders, it was merely a temporary obstacle. Once statehood was achieved, that legal status became the tool used to dismantle the partition plan itself—allowing them to reject its imposed borders, ignore its political limits, and abandon its premise of shared sovereignty.

Statehood also gifted the Zionist project something more powerful than territory: an Orwellian inversion of language through which the public is informed. From this position, Zionist terrorism became "self-defense," and Palestinians—simply by remaining on their own land—became "infiltrators" or "terrorists." The settler became the sovereign. The native became the threat. Any form of resistance, even refusal to disappear, was characterized as aggression.

When a state claims self-defense while crushing resistance to its own violence, all aggression becomes self-justified.

The following year, the same UN that enabled this dispossession issued its Universal Declaration of Human Rights—a document whose principles were already being systematically violated in Palestine.

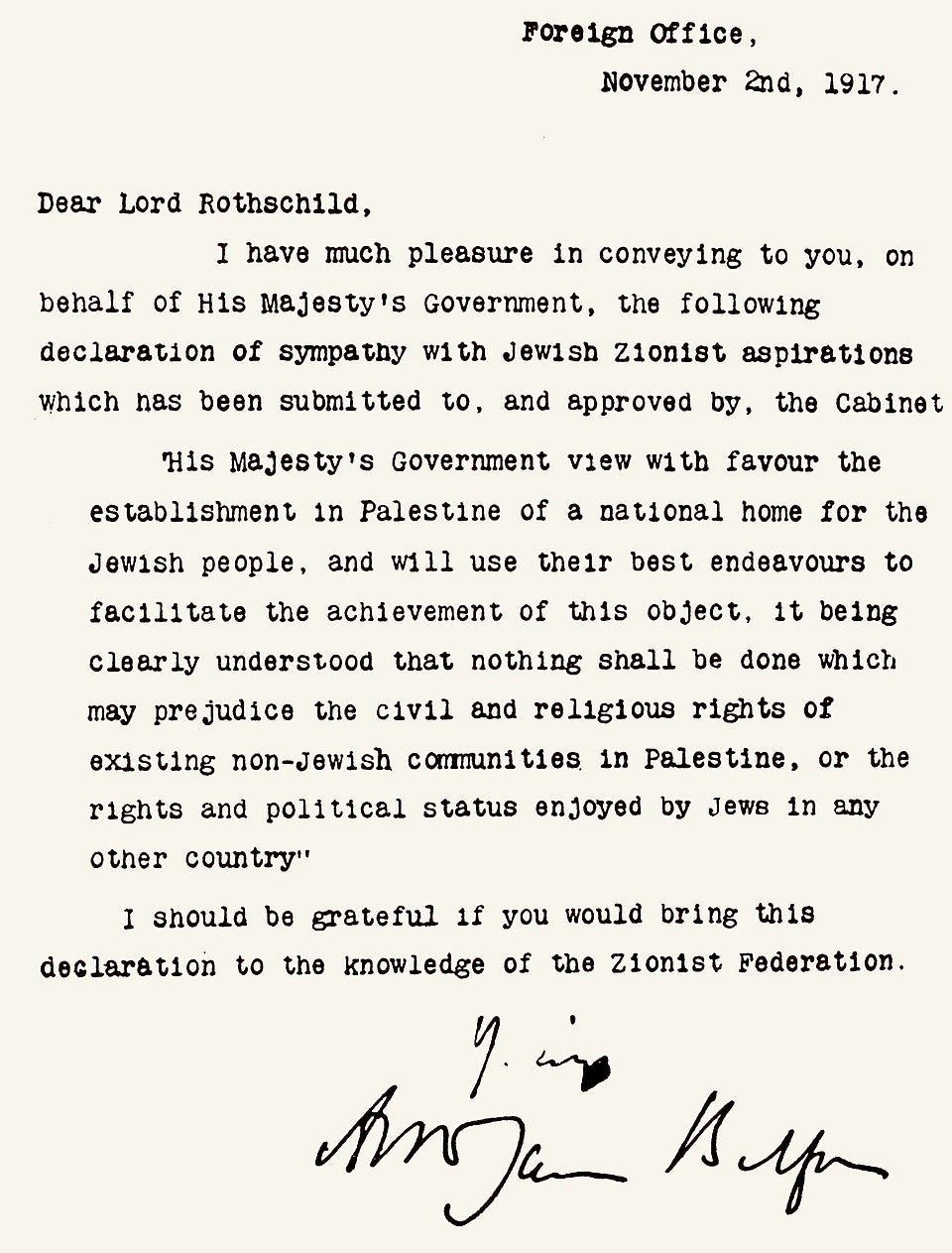

UN Resolution 181 perpetuated the logic of the Balfour Declaration issued 30 years before it, in 1917—a colonial promise repackaged under the banner of a new world order, shaped and enforced by the postwar victors who defined the global order on their terms.

The Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was just 67 words long, but its effects have lasted for over a century. In 1917, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour sent a letter to Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild, a prominent banker and British Zionist leader. It promised support for creating a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine. It also vaguely claimed that "nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities." This protection was never actually provided.

With quiet approval from U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, Britain made a colonial promise over land it didn't own to a movement it supported, while ignoring the Palestinian Arab majority already living there.

The Declaration wasn't an isolated document. It came right after the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, where Britain and France secretly divided control of Arab lands. More importantly, it gave official political backing to a European Jewish nationalist movement that had already begun to establish settlements.

The plan had been laid out decades earlier. In 1897, Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, organized the First Zionist Congress in Basel and wrote in his diary, "At Basel I founded the Jewish state. If I said this out loud today I would be greeted with universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will realize it." This wasn't just wishful thinking—it was a concrete plan. Herzl knew that Zionism needed imperial protection to succeed. From the beginning, the movement allied itself with colonial powers to gain the legitimacy it needed.

This wasn't a movement for coexistence, but a settler-colonial project—designed to take the land, remove its original inhabitants, and erase the Palestinian presence. This imperial transformation went beyond just territory; it changed Palestine physically, politically, and culturally—reshaping it according to the settlers' vision while making Palestinians invisible.

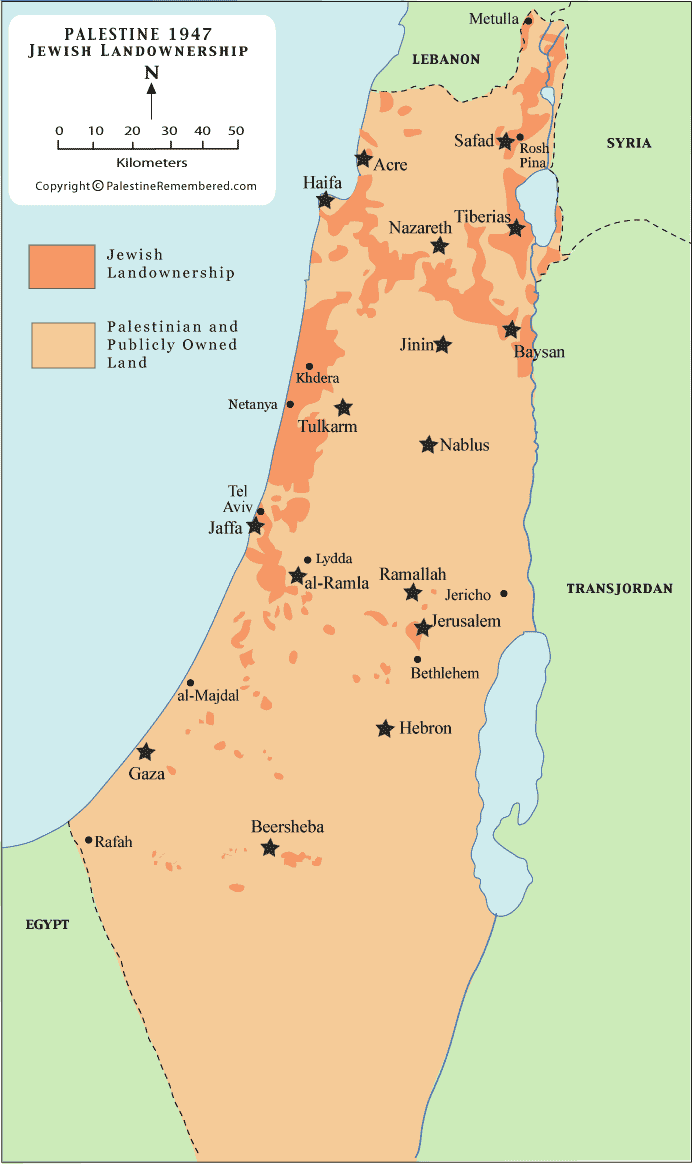

Land was bought mainly from absentee Arab landlords who lived outside Palestine, evicting local tenant farmers who had worked that land for generations, to make way for Jewish settlers.

At the time of the Balfour Declaration, Jews owned only about 2% of the land in Palestine. Through decades of systematic acquisition, this percentage grew to approximately 7% by 1947—yet the UN partition plan allocated them 56% of the territory. This dramatic disparity reveals how imperial powers privileged Zionist claims over Palestinian rights and presence.

Armed militias formed. Parallel institutions were built—not to integrate with existing society, but to replace it. The settler future was being constructed through systems of exclusion and control—even as the indigenous population remained present, increasingly confined, surveilled, and stripped of agency.

Before Political Zionism

"You are being invited to help make history.

It doesn’t involve Africa, but a piece of Asia Minor; not Englishmen, but Jews.

I turn to you because it is something colonial."

— Theodor Herzl, letter to Cecil Rhodes, 1902

An important historical distinction is often overlooked: Palestine had Jewish communities long before political Zionism began. Some Jews—particularly Sephardi and Mizrahi communities—had lived in Palestine for generations as part of its indigenous population, and others maintained spiritual ties through prayer and pilgrimage. Political Zionism, which emerged in the late 19th century, was something entirely different—a European-based movement with the distinct project of settlement and appropriation aimed at building a Jewish state.

These indigenous Jewish communities lived in cities like Al-Quds (Jerusalem), Al-Khalil (Hebron), Safad, and Tabariyya (Tiberias). They spoke Arabic, participated in the social and economic life of the land, and had no nationalist ambitions. These local Jews were neither white nor foreign, which complicated the entire narrative of "return." Their presence disrupted the messianic-colonial script of a people exiled and restored through European-Christian design.

As historian Nur Masalha wrote in Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History, "Until the advent of anachronistic European political Zionism at the turn of the 20th century, the people of Palestine (Arabic: sha'b Filastin) included Arab Muslims, Arab Christians, and Arab Jews. Being a rendering of the Israeli Zionist/Palestinian conflict, historically speaking the binary of Arab versus Jew in Palestine is deeply misleading.”

Zionism arrived from Europe with a political ideology foreign to their lives—one that sought not integration, but separation. Many opposed it outright, seeing it not as a return, but as a foreign colonial project.

Organized Jewish colonization of Palestine began about 140 years ago, in 1882, under the direct patronage of European wealth and imperial ambition. That year, Baron Edmond de Rothschild began personally financing and managing the implantation of European settlers onto Palestinian land.

Earlier attempts at settlement, such as Petah Tikva—founded in 1878 by Jewish immigrants from Europe on land near the Palestinian village of Mulabbis—failed due to harsh environmental conditions, diseases like malaria, and the resistance of the native Palestinian population.

The escalation came with the founding of Rishon LeZion in July 1882 by settlers from Kharkov in the Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine). When financial collapse threatened the settlement, Rothschild intervened in 1883, restructuring it as a managed colonial outpost under his direction.

In mid-1883, Rothschild again stepped in to finance a settlement south of Haifa founded in December 1882 by Romanian Jews. He renamed the settlement Zichron Yaakov in memory of his father James (Yaakov) Rothschild.

This was only the beginning. Between 1882 and 1917, two waves of organized colonization laid the foundations for a regime built on land theft, displacement, and the systematic replacement of a native people—one of the most brutal invasions ever forced onto an indigenous land.

These organized settlements built upon earlier precedents. In the mid-19th century, while political Zionism was still decades away from being formalized by Herzl, Western powers had already begun projecting their religious visions onto the Holy Land. These imperial projections would lay the groundwork for later colonial ambitions disguised as religious restoration.

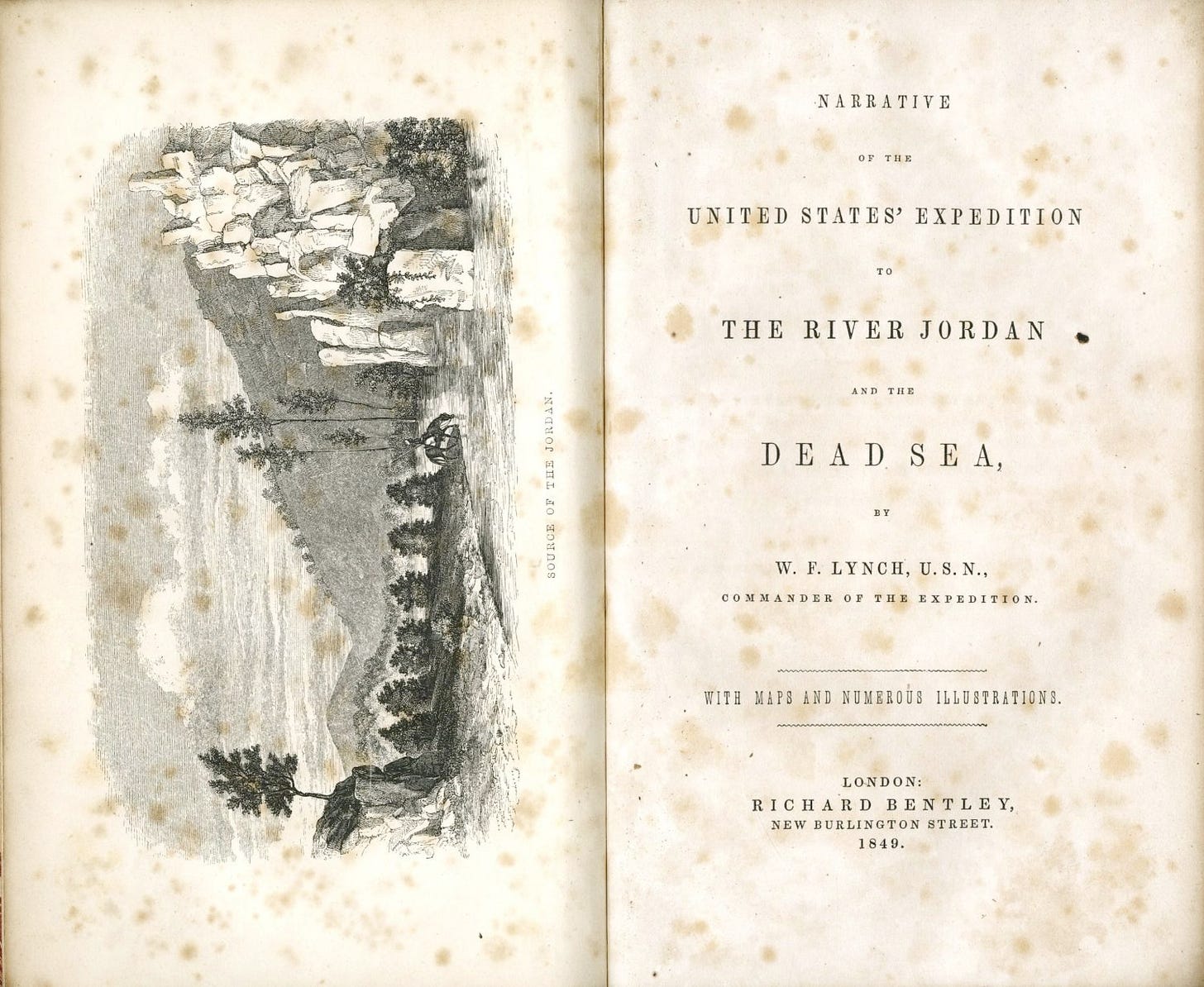

In 1848—half a century before Herzl's Congress and a century before the Nakba—the U.S. launched a state-backed mission to Palestine led by Lieutenant William Francis Lynch, a U.S. Navy officer with a history of mapping expeditions in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Although officially presented as a "scientific and hydrographic survey" to chart the Jordan River and Dead Sea region, the expedition was motivated by religious fanaticism and America's growing messianic vision, as Lynch's own writings would reveal.

In Narrative of the United States' Expedition to the River Jordan and the Dead Sea (1849), Lynch made his purpose clear, describing the operation as "conceived in the spirit of Christian enterprise… to illustrate and confirm the Holy Scriptures." Like Christopher Columbus and the Puritans before him, he viewed his task not as exploration, but as sacred duty—meant to prove the literal truth of Old Testament narratives and validate biblical geography.

It was less science than crusade—a fusion of nationalism, religion, and empire, carried out under the American flag in service of a messianic vision. This was imperialism's pseudo-rationality: confirmation bias masquerading as objectivity, and "knowledge" serving the work of domination.

To Lynch, Palestine was not a land of people and history, but a landscape frozen in religious time—awaiting redemption through Christian intervention and the fulfillment of a Jewish restoration, even though Jews already lived there.

Lynch interpreted natural features of the landscape as divine judgment rather than geological reality. In his eyes, the Dead Sea's barrenness wasn't due to its extreme salinity or low elevation, but rather divine punishment. He drew on the Book of Joel's prophecy that "The field is wasted, the land mourneth, and joy is withered from the sons of men." Observing the desolate landscape, Lynch marveled, "How literally is the prophecy of Joel fulfilled!" He was struck not by the land itself, but by how perfectly it seemed to confirm scripture.

Reflecting on the contrast between America and Palestine, he wrote, "The patriot may glory in the one," referring to the United States [meaning a patriot may take pride in America], "the Christian of every clime must weep, but, even in weeping, hope for the other." To him, Palestine had spiritually fallen under non-Christian rule, and "to ensure the restoration of the Jews to Palestine,”that, for him, was the point of it all.

Not everyone, however, was unaware of what the expedition represented. "There was little evidence of curiosity respecting us or the labour in which we were engaged," Lynch wrote in his journal on the first night in Jerusalem. "Our interpreter once or twice heard the remark, 'the Franks [Crusaders—a term locals used for Western European Christians since the medieval crusades, to distinguish them from native Christians] are preparing to take possession of the Holy City.'"

The irony of recording this without a hint of self-awareness lands somewhere between colonial blindness and accidental confession. Even as he framed his mission as sacred restoration, the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine already saw it for what it was: the opening act of colonization. The religious-imperial framework established in the 1840s would later evolve into the theological underpinnings of American evangelical support for Israel—a direct line from Lynch's "Christian enterprise" to today's faith-based foreign policy.

American Colonies in Palestine

The missionaries weren't far behind Lynch's expedition. Building on this earlier religious interest, in 1855, American evangelicals from Maine and Illinois established the first official U.S. colony in Jaffa. Known as the Adams Colony, after George J. Adams—a charismatic preacher and former Mormon who had formed his own sect—they brought 150 settlers, driven by millenarianism: the belief that Christ's return could be hastened by preparing the land for the Jews.

Two years earlier, in 1853, Clorinda Minor had already established Mount Hope, a small agricultural colony near Jaffa. An American follower of William Miller's apocalyptic movement—a popular American preacher who initially predicted Christ's return in 1843 and then revised it to 1844—she had waited for the fulfillment of Miller's end-time prediction during what became known as the Great Disappointment.

When the promised apocalypse never came, she didn't abandon the prophecy—she reinterpreted it. If Christ wasn't coming to the world, perhaps the world had to be made ready for Christ.

So she sailed to Palestine.

With a handful of American and German settlers, Minor established a farm, the goal of which wasn't integration or coexistence but "redemption"—teaching Jews to cultivate the land, restoring it to faith-derived productivity as imagined in scriptural accounts, and preparing the ground for the Second Coming. The aim was theological, not agricultural. Palestine was not a homeland for Jews—it was a staging ground for Christian prophecy.

Both colonies struggled from the start. Mount Hope faced drought, disease, and resistance from the surrounding communities. It collapsed in 1858. The Adams Colony fared no better, disintegrating within five years. Though rarely remembered today, they were early attempts in a longer arc of settlement projects to overwrite Palestine—one failed prophecy layered over another.

While these collective efforts faltered, individual zealots proved equally determined in their messianic missions. Perhaps no figure captures the intensity and absurdity of American messianism better than Warder Cresson. A Philadelphia Quaker turned apocalyptic visionary, he managed in 1844 to get himself appointed as the first U.S. consul in Jerusalem—a distinction as brief as it was grandiose. Washington rescinded the appointment just days later, once officials realized how eccentric their new diplomat really was.

Cresson, however, wasn't one to let bureaucratic hesitation interfere with divine calling. He journeyed to the Holy Land anyway, planted the American flag in Jerusalem's soil, and declared that God was gathering the Jews back to Zion as a prelude to the end of days.

In 1848, he converted to Judaism, renamed himself Michael Boaz Israel, and sought to join the very community he believed he had been sent to champion.

He briefly returned to Philadelphia—where his family put him on trial for insanity. He won, sailed back to Jerusalem as a self-declared Jewish pioneer, and spent the rest of his life there, establishing charities and farming projects for the city's poor Jews.

He died in 1860 and was buried on the Mount of Olives. His life was part pilgrimage, part performance—but entirely American in its fusion of religious zeal, personal myth, and imperial projection.

The Colonial Roots of Biblical Archaeology

Before Cresson, there was Robinson.

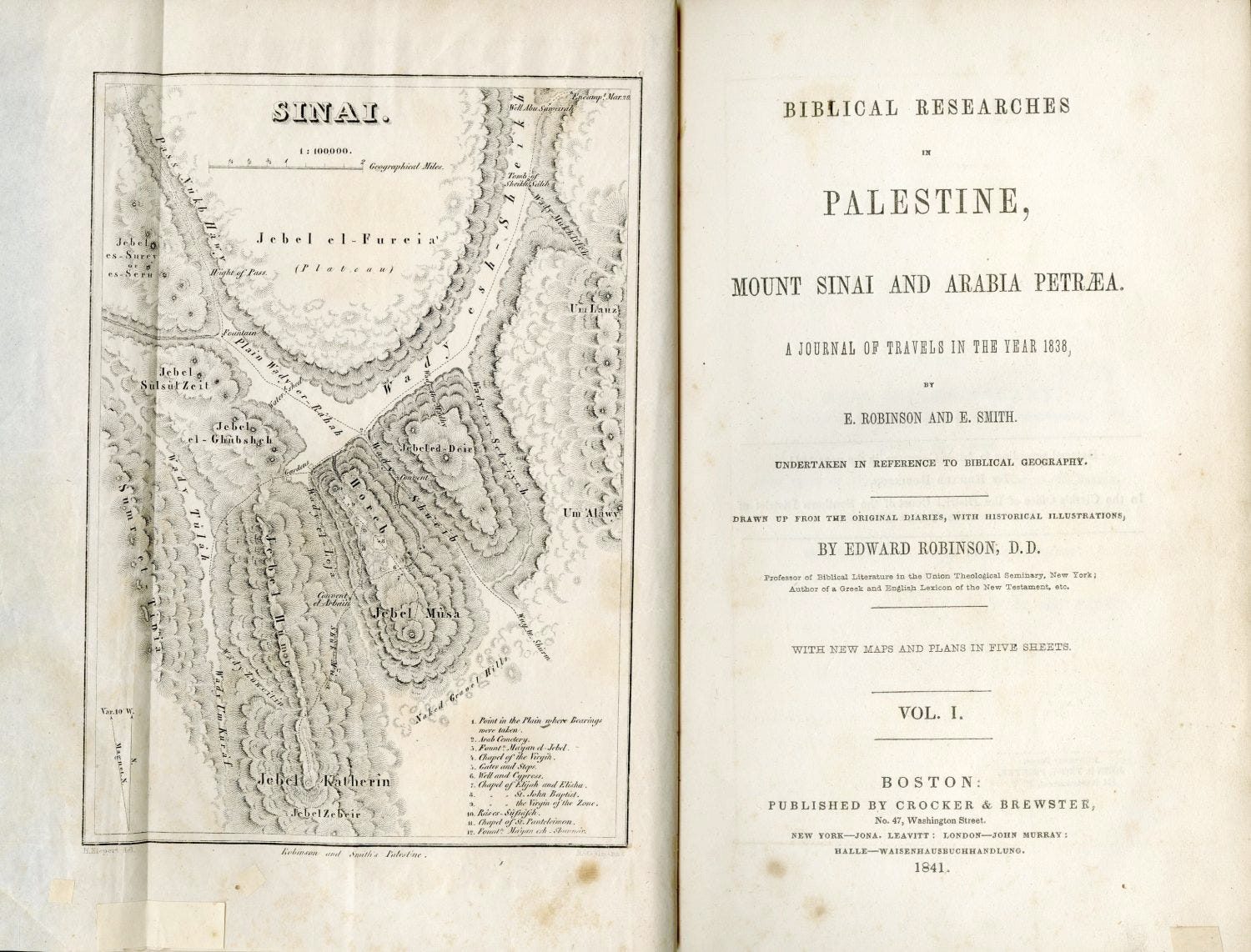

In 1838, Edward Robinson, an American theologian and Orientalist, toured Palestine with a mission: to locate Old Testament sites and restore the land's sacred geography. Armed with a Bible and a list of Arabic place names, Robinson claimed to "rediscover" cities long vanished. His 1841 book, Biblical Researches in Palestine, became the cornerstone of what he called biblical archaeology—but it was less excavation than erasure.

Robinson wasn't searching for Palestine. He was searching for Israel. He looked past the people in front of him and named the ruins beneath their feet. Rather than engaging with the land as a complex, inhabited place with layered history, he approached it as a dormant religious archive awaiting Western interpretation. His work presented itself as empirical, but it was anything but neutral.

As Edward Said argued in Orientalism (1978), Robinson's approach exemplified not disinterested scholarship but a "Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient." Where Cresson's messianic journey reflected personal religious zeal, Robinson's systematic approach laid the groundwork for an academic tradition that would shape Western scholarship for generations—and provide intellectual justification for colonial claims.

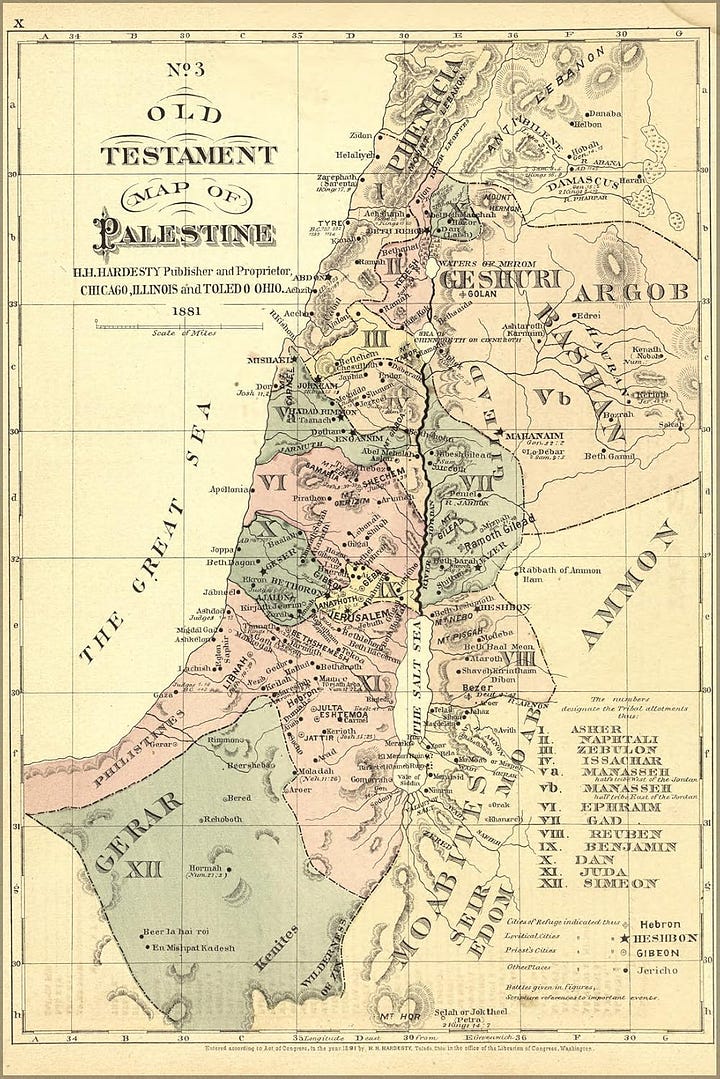

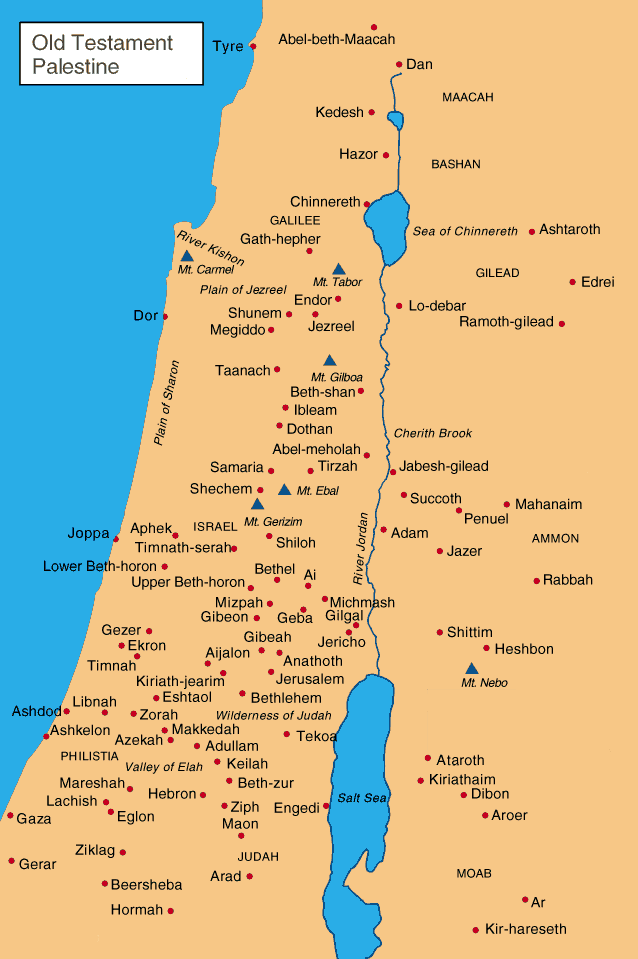

Robinson filtered Palestine through prophecy, ignoring its political, cultural, and historical complexity. He dismissed Ottoman records and Arab oral traditions as "Mohammedan corruptions," privileging Protestant imagination over indigenous knowledge systems. His method relied on phonetic substitution: hearing "Jeba" and declaring it the scriptural "Gibeon," or equating "Beisan" with "Beth-shan."

His interpreter and guide, Eli Smith—an American missionary based in Beirut—played a central role in this process. Fluent in Arabic and embedded in the region, Smith's linguistic expertise became a colonial tool, enabling Robinson to reframe living names as biblical remnants. Rather than serving as a cultural bridge, Smith functioned as a mechanism of appropriation—using language to overwrite the present with a biblical past.

These linguistic appropriations weren't academic exercises—they were acts of textual conquest that preceded physical displacement. By renaming places according to Judeo-Christian geography, Robinson created a paper claim to the land, one that would later be used to legitimize actual occupation. His work made Palestine legible to Western powers as "biblical Israel," rendering Palestinian presence a temporary interruption in a divinely ordained historical narrative.

As Nur Masalha writes in Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History (2018), "This was not an objective enterprise; it was a Protestant religious-historical venture that privileged the Bible over native knowledge systems." These reassignments ignored archaeology and erased meaning—an act of territorial appropriation that transformed living Arabic into dead Hebrew, present communities into ancient ghosts. Arabic place names weren't corruptions of biblical names; they had their own meaning and history. They described landscape features, farming practices, and local stories–all reflecting the lives of the people who had inhabited the land for generations.

Robinson's influence extended far beyond academia. He established a colonial model of knowledge production that would be carried forward a century later in Zionist cartography. When Israeli institutions systematically replaced Arabic place names with biblical ones after 1948, they were completing what Palestinian geographer Salman Abu Sitta described as "cartographic ethnic cleansing"—renaming the land to fit a Western script and severing it from its cultural and historical context.

The consequences of this naming warfare can be seen in cases like the Palestinian village of Qatra, which Robinson identified with the Old Testament Gedera. In 1948, Qatra was depopulated and destroyed; a Jewish town—Gedera—was built in its place. Similarly, the Palestinian village of Lubya was renamed Lavi, and Yibna became Yavneh to match scriptural phonology. More recently, this practice continues with places like Susiya in the South Hebron Hills, where Palestinian homes were demolished after the area was declared an "archaeological site" of religious-historical significance.

So when did this really begin? What is today called a conflict began when Palestine was reimagined as a canvas for messianic destiny—long before 1948, before the Nakba, before the Balfour Declaration, and even before Herzl's political Zionism. It began in the 19th century when American and European scholars used the Bible to claim and colonize the land intellectually before settlers arrived physically.

This scholarly enterprise produced an epistemic Nakba—a catastrophe of knowledge—that preceded and enabled the physical Nakba. By writing Palestinians out of history and presenting the land as essentially Jewish, Western scholarship created the intellectual framework that transformed ethnic cleansing into "restoration" and made dispossession appear as historical justice.

This process of historical erasure prompted critical responses from scholars who recognized its political implications. British biblical scholar Keith W. Whitelam directly challenged this re-mapping of Palestine. He criticized scholars who refer to the land as "Palestine" yet never refer to its inhabitants as Palestinians—a denial, he argued, that amounted to the silencing of Palestinian history.

In The Invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History (1996), Whitelam wrote, "The inhabitants are for the most part anonymous, only taking on an identity when they become Israelite or Judaean. It is possible to refer to the 'Palestinian coastline', 'Palestinian agriculture', or the 'Palestinian economy', but the inhabitants are never described as Palestinian."

He argued this practice confines "the notion of a 'Palestinian history'… to the modern period, as if the ancient past has been abandoned to Israel and the West."

Ancient inhabitants are labeled with archaic terms—Canaanites, Amorites—or defined only in relation to Israel, never as Palestinians in their own right. This, Whitelam contends, reflects a refusal to acknowledge an ancestral identity for the indigenous people of ancient Palestine.

Palestinians were stripped of their identity before they were stripped of their land. The broad ethnic term "Arabs" was used as a tool of expropriation, portraying the indigenous people of Palestine as indistinct fragments within a vast Arab mass. By dissolving their specificity into this larger collective, the theft of their land could be presented not as expulsion, but as something natural—even compassionate.

"The history of ancient Palestine has been ignored and silenced by devotional studies because its object of interest has been an ancient Israel conceived and presented as the taproot of Western civilization." Whitelam concluded that "biblical studies is, thereby, implicated in an act of dispossession which has its modern political counterpart in the Zionist possession of the land and dispossession of its Palestinian inhabitants.”

This academic exclusion created a narrative void in which the region's inhabitants could be rendered invisible—first in scholarship, then in policy, and finally on the land itself. Without historical recognition, Palestinians become, as Whitelam described, "unimportant, irrelevant, and finally non-existent.”

Whitelam's analysis went beyond abstract academic arguments. He showed how the silencing of Palestinian history was carried out by institutions like Britain's Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF), which embedded this systematic erasure of Palestinian identity and history into imperial maps and surveys that redefined the land itself.

Through selective labeling, strategic omissions, and biblical overlays, these supposedly scientific documents transformed Palestine into a land awaiting Jewish restoration rather than one continuously inhabited by its indigenous people. This cartographic erasure completed the circle that began with biblical scholarship, creating both the intellectual framework and the practical tools that would enable Palestine's physical occupation in the decades to come.

The Palestine Exploration Fund and British Mapping

Robinson's methodology endured and was refined by his successors. Most notable amongst them was French archaeologist and biblical scholar Victor Guérin, who shared Robinson's belief that Arabic place names preserved echoes of "ancient Israel." Despite being Catholic, Guérin operated within the Protestant biblical-colonial tradition, demonstrating how religious motivations transcended denominational boundaries and converged with imperial mapping and control.

From 1852 to 1888, Guérin led numerous expeditions throughout Palestine. These journeys produced the seven-volume Description Géographique, Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine—an exhaustive catalog of place names, ruins, and oral traditions that continues to influence Western biblical scholarship today.

Guérin's work formed part of a broader intellectual network, including institutions such as Jerusalem's École Biblique (founded in 1890), all aligned with the Palestine Exploration Fund's (PEF) objectives. This network would soon gain institutional power through the PEF, which formalized and expanded the approach pioneered by Robinson and Guérin. Collectively, these scholars and organizations replaced Palestine's living geography with a biblical fantasy—one mapped through scripture rather than history.

Established in 1865 by a coalition of British officers, biblical scholars, and colonial administrators, the PEF merged religious imperatives with strategic objectives. Backed by the Royal Engineers, the engineering arm of the British Army, and endorsed by the Church of England, it presented itself as a scientific enterprise—but its mapping served distinctly political ends.

Contradictions marked the PEF's mission from the beginning. At its inaugural meeting in 1865, Archbishop of York William Thomson declared that the organization was "strictly an inductive inquiry" and "not to be a religious society." He presented the endeavor as empirical and objective, divorced from religious interpretation.

Yet in the same speech, he described Palestine as "the country in which the documents of our Faith were written" and called the land "essentially ours." This possessive language exposed the underlying colonial mindset. Quoting the biblical promise to Abraham—"Walk through the land in the length of it and in the breadth of it, for I will give it unto thee"—he defined the expedition as a divine return to a land already promised.

He urged supporters to undertake a "new crusade" and spoke of a "sacred duty" to recover the land's history. These were not rhetorical flourishes but declarations of purpose.

These contradictions revealed the PEF's true agenda. The land was presumed sacred before it was surveyed; the expedition did not seek discovery but confirmation. This approach embodied what scholars would later call the biblical maximalist tradition: treating the Old Testament as historical record awaiting field verification. Geography became theology by other means. Every recovered place name and cataloged ruin served a dual purpose: as supposed evidence of scripture, and later, as justification for settler-colonial appropriation.

Charles Warren and Claude Conder, both British military officers, became the Fund's most influential field operatives. Warren began his surveys of Jerusalem in 1867, excavating beneath the city in search of biblical foundations. Meanwhile, Conder directed the Survey of Western Palestine from 1872 to 1877—an effort that ranked among the region's most ambitious cartographic undertakings.

With British War Office support, Conder's team mapped more than 6,000 square miles, producing charts that merged scriptural reference with military precision. His reports blended religious text with strategy. Unlike Robinson's speculative readings or Guérin's methodical cataloging, Conder brought systematic structure and institutional backing.

He anchored biblical stories to geographic coordinates, such as identifying Tel Es-Sultan (an archaeological mound near Jericho) as Joshua's conquered city despite archaeological contradictions. His team designated the hills of Nablus as the biblical territory of Ephraim, selectively emphasizing topographical features that appeared to validate scripture.

Under Conder's leadership, Palestine was rendered legible to empire. Its landscape was realigned with religious narrative—mapped, claimed, and prepared for possession.

Their maps depicted Palestinian villages as temporary, while ancient ruins were framed as proof of Jewish antiquity. What Robinson had initiated linguistically, the PEF completed institutionally—translating biblical imagination into imperial blueprint.

Eventually, this ambitious enterprise confronted undeniable limitations. What had begun as devotional cartography escalated into full-scale archaeological excavation. Despite exhaustive name substitution and attempts to match ruins to scriptural dimensions, the physical evidence remained stubbornly uncooperative.

Excavations repeatedly failed to uncover material evidence for key biblical events like the conquest of Canaan or Solomon's empire. Dating methods showed settlements existing at different periods than biblical chronology required. Artifacts revealed cultural connections to surrounding civilizations rather than the distinct Israelite society described in texts. Scriptural myths had been forcibly superimposed onto Palestine's landscape—but the terrain consistently resisted this manufactured interpretation.

The Collapse of Biblical Certainty

“The conclusion accepted by a majority of the new archaeologists and Bible scholars was that there never was a great united monarchy and that King Solomon never had grand palaces in which he housed his 700 wives and 300 concubines. The fact that the Bible does not name this large empire strengthens this conclusion. It was late writers who invented and glorified a mighty united kingdom, established by the grace of the single deity.”

—Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People (2008)

Put simply, the evidence never came. What they were looking for wasn't there.

At the center of biblical archaeology's development was William F. Albright, an American archaeologist and devout Protestant who arrived in Palestine in 1919 and quickly rose to prominence. For decades, he shaped what became known as the Albright School—a method that treated archaeology as a means of confirming the Bible.

He maintained that the biblical narrative, particularly the Old Testament, was historically reliable unless proven otherwise. This presumption of biblical accuracy would eventually collide with mounting evidence against it.

Albright's influence extended through a generation of scholars—including G. Ernest Wright and George Mendenhall—who carried his approach into American biblical scholarship, theology departments, and Zionist-aligned research institutions. Biblical sites were identified, walls were dated, and events were interpreted to match scriptural accounts, inverting proper scientific methodology by starting with biblical conclusions and selectively using—or ignoring—evidence to elevate these narratives to historical fact.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, this framework remained dominant despite mounting contradictory evidence. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls (1946-1956) revealed textual variations that challenged the idea of a single, divinely preserved biblical text. They contained multiple versions of biblical books with significant differences, alternative religious texts not included in the canon, and evidence of diverse theological perspectives within Second Temple Judaism.

Rather than confirming biblical history, these materials suggested a much more complex development of Jewish religious thought than the linear narrative presented in traditional scholarship.

By the 1980s, a new generation of archaeologists including Israel Finkelstein and William Dever began to challenge Albright's paradigm. They advocated for archaeological methods independent of biblical confirmation. Advanced scientific techniques further solidified this shift. Radiocarbon dating, archaeometallurgy (the study of ancient metalworking), residue analysis, and satellite archaeology provided precise chronologies and material evidence that couldn't be dismissed as interpretive bias. When multiple independent dating methods placed key sites and artifacts in periods inconsistent with biblical narratives, the discrepancies became scientifically undeniable.

These methods transformed archaeology from comparative guesswork to empirically verifiable science, rendering theological frameworks increasingly untenable. The promised evidence had not materialized. Instead, the ruins consistently told a different story.

Site after site revealed contradictions to the biblical narrative. At Hazor (1955-1958), archaeologist Yigael Yadin initially claimed to have found evidence of Joshua's conquest, but later research revealed the destruction layer dated to a different period entirely.

At Gezer (1964-1974), structures once triumphantly attributed to Solomon's building campaigns were later redated to the 9th century BCE—generations after Solomon's purported reign.

The "Solomon's stables" at Megiddo, long attributed to the biblical king, were similarly shown to date from the 9th century BCE, well after Solomon's purported reign.

The conquest narratives fared no better under scientific scrutiny. At Jericho, Kathleen Kenyon's excavations in the 1950s showed that the city's walls had collapsed centuries before Joshua's supposed arrival. Similarly, excavations at Ai revealed the site was abandoned during the period when biblical Joshua supposedly conquered it. Settlements in Canaan showed cultural continuity rather than the abrupt disruption that would accompany a large-scale invasion, suggesting indigenous development rather than external conquest.

The Exodus story suffered the same fate. Archaeological surveys of the Sinai Peninsula, where the Israelites supposedly wandered for 40 years, revealed no evidence of large-scale encampments or material culture from the purported exodus period. Egyptian records, meticulous in documenting population movements and military activities, contained no mention of a mass departure of enslaved Israelites.

Shlomo Sand, an Israeli historian and professor at Tel Aviv University, summarized these findings definitively, stating, "Archaeological findings provide no indication of a massive migration from Egypt. Not a single shard of pottery or scrap of Hebrew writing has been discovered in the Sinai Desert from the supposed forty years of wandering" (The Invention of the Jewish People).

In an interview with Le Monde Diplomatique, Sand reflected on his own scholarly journey, saying, “As I pursued my research, my realization that the Exodus from Egypt never happened and that the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Judah were not exiled by the Romans, left me nonplussed.”

The image of a grand united monarchy under David and Solomon—defined by monumental construction and centralized rule—also lacked meaningful archaeological support. "Explorations at all the other sites that were opened up around [Temple Mount] failed to find any traces of an important tenth-century [BCE] kingdom, the presumed time of David and Solomon. No vestige was ever found of monumental structures, walls or grand palaces,” noted Sand in The Invention of the Jewish People.

Sand further pointed out the absence of evidence for the most sacred structure in biblical narrative. "Unfortunately, we have no archaeological evidence of the existence of a First Temple,” he wrote in The Invention of the Land of Israel (2012). This absence is particularly significant given the temple's central importance in biblical stories about Solomon's reign and its role in justifying contemporary claims to Jerusalem.

By the late 20th century, biblical archaeology's foundations crumbled beneath the weight of evidence. The stories that justified colonization had no archaeological support: no exodus trail through Sinai, no conquest of Canaan, no grand Davidic kingdom, and no trace of Solomon's Temple.

No trails. No conquest. No empire. No Temple. The science had spoken clearly—the central biblical narratives used to justify claims to the land simply weren't supported by physical evidence—but the politics refused to listen.

This scholarly crisis carried profound political implications. If the biblical kingdom of David and Solomon could not be verified archaeologically, what remained of Israel's historical claim to the land? If the conquest narratives were literary rather than historical, how could they validate modern territorial expansion? The discrediting of biblical archaeology threatened not just academic paradigms but the ideological foundations of the Israeli state itself.

This explains why, despite academic consensus shifting away from biblical maximalism, Israeli institutions and settlement organizations continue to promote archaeological interpretations that justify settlement expansion—even in direct contradiction to overwhelming archaeological evidence. When science fails to validate ideology, the response is not to abandon the claim, but to abandon science.

The Minimalist Revolt

By the 1990s, biblical archaeology faced a reckoning. The "minimalist-maximalist controversy" wasn't just academic debate—it was the collapse of an entire colonial enterprise operating under the veneer of scholarship. After decades of contradictory evidence, scholars finally confronted the obvious: the field existed to legitimize settler-colonial theft, not discover truth.

The critique began taking shape in the early 1990s through the groundbreaking work of several key scholars. Philip R. Davies, Thomas L. Thompson, Niels Peter Lemche, and Keith Whitelam collectively exposed biblical archaeology as a politically-motivated enterprise. Their research demonstrated how archaeological findings were consistently subordinated to ideological objectives that supported Zionist territorial expansion and settlement.

In his work In Search of "Ancient Israel" (1992), Davies provided one of the movement's clearest and most influential statements, writing, "Historical Israel exists only in archaeological remains, biblical Israel exists only in scripture. 'Ancient Israel' exists only as an unacceptable amalgam of the first two."

These scholars, who came to share the "minimalist" label, systematically dismantled the field from different angles. Davies focused on literary construction, revealing how post-exilic writers invented "Ancient Israel" to serve theological and political agendas. His work exposed the textual mechanisms behind the mythmaking.

Lemche complemented this by addressing chronological problems, demonstrating that biblical texts were composed centuries after the events they purported to describe. This temporal gap made these sources inherently unreliable for historical reconstruction.

Thompson concluded in a 2009 article for Holy Land Studies that "Zionist and, later, Israeli politics of nation-building has strongly influenced 'biblical archaeology' and has significantly undermined the integrity of [its] scholarship." He explicitly called for "the independence of Palestinian archaeology from biblical studies; that is, an end to biblical archaeology." This radical proposal acknowledged the field's fundamental corruption.

In The Invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History, Whitelam directly confronted the colonial foundations of biblical scholarship. What was presented as neutral science, he wrote, was "an act of interpretation presented as objective scholarship, carrying the full weight of Western intellectual institutions."

He argued that this scholarship was "intricately bound to the dominant understanding of the present in which the modern state of Israel has made an 'empty' and 'barren' land blossom"—with archaeological institutions advancing political aims through a portrayal that cast Palestine as a land without a people, redeemed by Zionist settlement, and used to reinforce the myth of "making the desert bloom."

In no uncertain terms, Whitelam and others portrayed classical biblical archaeology as a pseudo-scholarly charade—"faked scholarship" propped up by colonialist ideology. Their critique was not academic nitpicking; it was a direct challenge to a system of historical fabrication designed to erase Palestinian presence and legitimize dispossession.

The impact of the minimalist critique eventually reached even mainstream Israeli archaeology. By the early 21st century, prominent archaeologists like Israel Finkelstein had abandoned biblical literalism. Many adopted what might be called a "moderate minimalist" position, acknowledging the evidence while trying to salvage some historical core.

Thompson noted that as early as the 1970s there was a "paradigm shift"—a growing insistence that the archaeology of the region must disentangle itself from the Bible's account. The minimalist critique had deeper roots than many recognized, having gradually built momentum as evidence mounted against biblical maximalism.

The political implications of this shift can be seen in the deliberate terminological changes at leading academic institutions. Traditional biblical archaeology has increasingly given way to more objective approaches labeled as "Syro-Palestinian archaeology" or "archaeology of the Southern Levant." These changes move away from biblically-centered frameworks toward scientific methodologies that examine the region's history on its own terms, challenging the Judeo-ethnocentrism which dominates nationalist Israeli claims on the heritage of ancient Palestine.

Nevertheless, as Davies dryly notes, when sensational claims still arise linking archaeological finds to scripture, "We have just another example of the old 'Biblical archaeology.'" This method, thoroughly discredited by serious historians, remains essential to maintaining the Zionist narrative—illustrating how political necessity continues to override scientific consensus when territorial claims are at stake.

Institutionalizing Archaeological Fiction

The collapse of biblical archaeology left a vacuum the Israeli state rushed to fill. As scholarly foundations crumbled beneath the weight of evidence, their ideological function was preserved as a dogmatic state strategy. Rather than abandoning their biblical interpretations when faced with contradictory scientific findings, archaeologists and institutions developed a systematic approach to maintain the narrative despite the evidence.

Palestinian archaeologist Dr. Abed Al-Razeq Matani calls this "historical engineering," not research. In Archaeology and the Industry of History (2011), he detailed how "Torahist" archaeologists deployed selective preservation and interpretation to prop up a fabricated construct of ancient Jewish dominion designed to rationalize modern colonization, despite exhaustive excavations finding no traces of a grand, centralized Jewish empire—only modest, scattered settlements embedded within the broader Canaanite and Philistine civilizations.

A systematic doctrine emerged as Israel reclassified ruins, rewrote laws, and renamed the land. Wells became "biblical," trees became proof, stones became claims. Museums, ministries, and media reinforce this constructed mythology—designed not to preserve heritage but to consecrate entitlement.

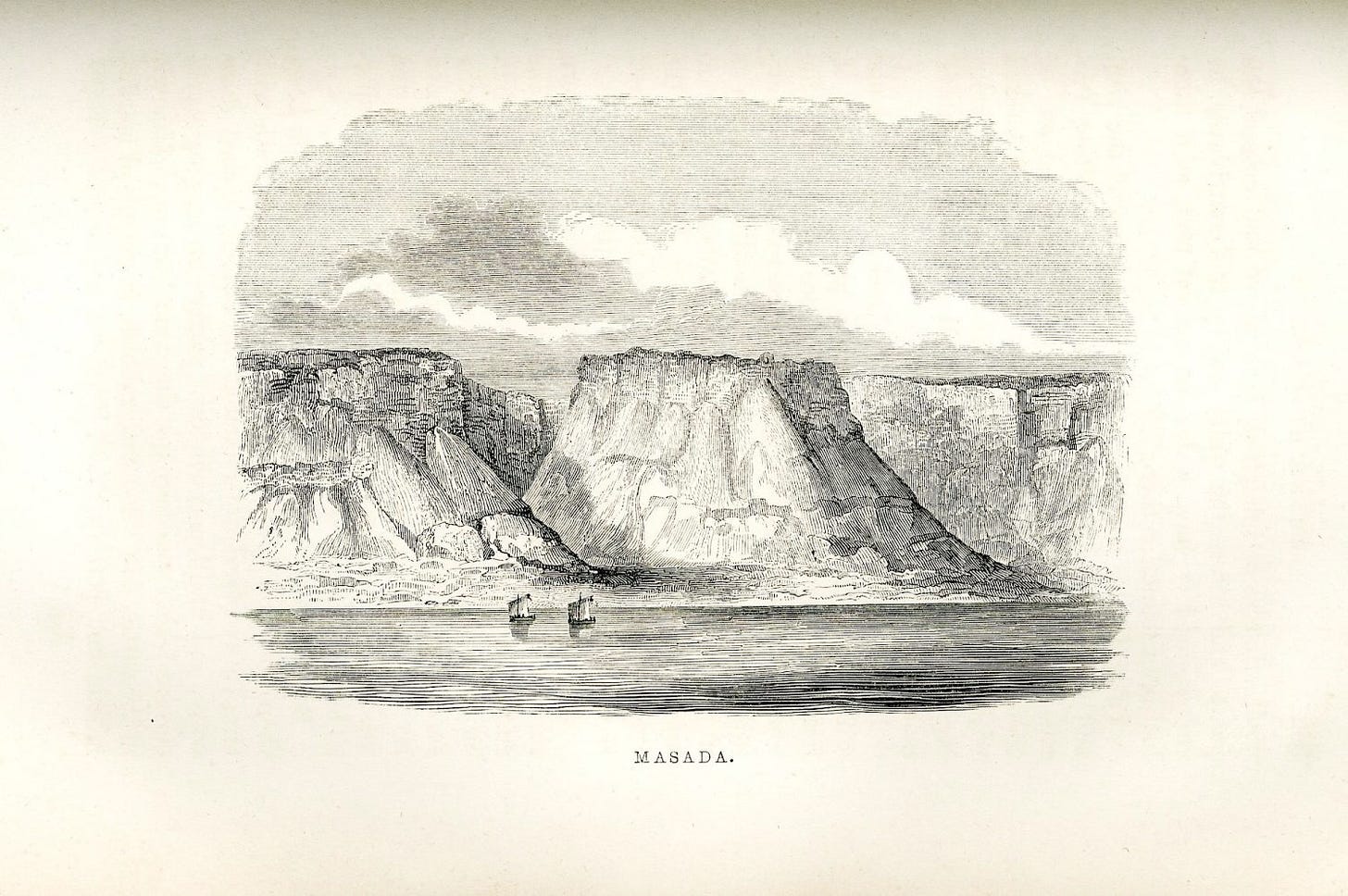

This inheritance myth wasn't just planted in the ground—it was instilled in generations through education and ritual. To this day, schoolchildren are led to staged digs to "rediscover" their sacred past, while soldiers march through Masada—an ancient fortress where, according to Israeli national mythology, Jewish rebels chose mass suicide rather than surrendering to Roman forces—reenacting martyrdom, chanting, "Masada shall not fall again." This ritualization transforms contested archaeological interpretations into unquestioned national doctrine.

Even Israeli sociologist Nachman Ben-Yehuda exposed this fabrication in The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel (1995), revealing how this foundational national story was deliberately constructed despite having no archaeological evidence of mass suicide.

He wrote about Yigael Yadin, the lead Israeli archaeologist who excavated Masada, "There can be very little doubt that Yadin, followed by others, constructed interpretations for Masada that supported the Masada mythical narrative, which is a political ideological narrative. This was accomplished not by falsifying any of the factual finds or artifacts, but by contextualizing these findings within the mythical narrative.”

The case of Al-Buraq Wall (the Western Wall) is one of the clearest examples of how Zionist archaeology has been exploited to forge political myths and suppress Palestinian history.

The portrayal of the Wall as a surviving remnant of the ancient Jewish Temple is a modern invention. Prior to 1967, even Zionist archaeologists did not seriously claim that the Wall was an actual part of the First or Second Temple. Much of what is today called the "Western Wall" was buried underground, unexcavated, and treated primarily as Islamic religious property.

During the British Mandate, the Shaw Commission (1930) explicitly affirmed that "all components of the Haram al-Sharif's (the Islamic holy site that includes Al-Aqsa Mosque) western wall remained Islamic property alone, due to its sanctity to Muslims," permitting Jewish prayer merely as a courtesy rooted in longstanding tradition, not sovereignty.

Immediately after occupying East Jerusalem in 1967, Israeli authorities launched sweeping excavation projects to reinvent the Wall's context, physically and symbolically.

The Mughrabi (Moroccan) Quarter, a historic Palestinian neighborhood founded in the 12th century by Salah Al-Din (Saladin) as a charitable endowment (waqf) for North African Muslims, stood directly in front of the Wall. In June 1967, Israeli bulldozers obliterated the neighborhood in a matter of days, destroying more than 135 Palestinian homes and forcibly displacing hundreds of residents to create the Western Wall Plaza.

No warnings were given. No protections were observed. A living neighborhood, with nearly eight centuries of continuous history, was reduced to rubble overnight to make way for a new national-religious conception.

This destruction represented not just physical demolition but a deliberate rewriting of history. In Heritage, Nationalism and the Shifting Symbolism of the Wailing Wall (2009), historian and cultural heritage expert Simone Ricca explained that these projects aimed to "erase a centuries-old Arab past and replace it with a new, exclusively Jewish space adapted to the symbolism of a modern Jewish state."

He further warned that Israel's excavation policies sought "to create a new reading of the Old City of Jerusalem, in which the Arab-Muslim presence was increasingly marginalized, and Jewish-Israeli identity exclusively affirmed," deliberately attempting to "project an image of Jewish continuity and Arab discontinuity."

Thus, the Al-Buraq Wall—once part of a pluralistic, multilayered Jerusalem—was violently reimagined as the centerpiece of an exclusive colonial mythology, its Palestinian and Islamic history buried under excavators, machinery, and propaganda. What could not be proven by the stones was manufactured by the narrative.

The 1978 Antiquities Law

The Al-Buraq Wall transformation exemplifies a much broader pattern of systematic erasure enacted through multiple mechanisms.

Physical erasure came first, with over 530 Palestinian villages demolished after the Nakba (documented extensively in Walid Khalidi's seminal work All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (1992)).

Legal erasure followed through the 1978 Antiquities Law, which declared anything built after 1700 CE—Islamic, Ottoman, Palestinian—"irrelevant" to heritage protection. What served the biblical ideology was preserved; everything else was destroyed.

These practices intensified following Israel's occupation of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem in 1967, and have expanded systematically in the decades since—particularly accelerating with settlement expansion in the 1990s and after the Second Intifada in 2005.

Excavations selectively preserve "biblical" layers while destroying Islamic, Arab, and Palestinian Christian evidence. As Matani wrote, "Israeli archaeology is nothing but a tool through which Israeli politicians and thinkers sought to validate their claims and impose them on the ground in order to Judaize the place and impose settler and Israeli sovereignty over Palestine."

These critiques gained recognition among Israeli scholars. Archaeologist Raphael Greenberg of Tel Aviv University criticized politically motivated archaeology in Jerusalem, observing, "Israeli archaeologists have given up many of their best practices in order to answer the continuing demands of mainly political actors" (Reuters, March 2010).

He further noted, "Archaeological heritage is mobilized to advance the Israeli national project, while the heritage of the local Arab population is erased or marginalized" (Towards an Inclusive Archaeology in Jerusalem: The Case of Silwan/The City of David (2012)).

Greenberg's assessment confirms what Palestinian scholars have long argued: archaeology in Israel has been weaponized, serving political agendas rather than historical understanding.

Defenders of these practices often claim they are simply preserving Jewish heritage sites threatened by development or neglect. However, as Aren Maeir, professor of archaeology at Bar-Ilan University and director of the Tell es-Safi/Gath excavation project, argued, this selective approach contradicts fundamental archaeological principles. "One must relate to the [past] as the archaeologist relates to the multi-period tell site, consisting of various periods, layers, cultures, and even intrusive elements" (Tell es-Safi/Gath I: Report on the 1996–2005 Seasons (2012)).

In archaeological terms, a "tell" is like a layered cake of ancient settlements—each representing a different civilization built upon its predecessors. Using this principle, Maeir challenges the political pressure to privilege biblical-period finds over other historical layers, emphasizing the ethical imperative to document all periods with equal rigor.

Maeir, speaking from within the Israeli archaeological establishment, has been explicit about the field's politicization. In a 2023 interview, he warned that "archaeology is very often used for non-archaeological, ideological agendas—whether religious, nationalist, et cetera..." He further acknowledged that "archaeology was used and misused as part of the national ideology of the Zionist movement—in fact up until today.”

This colonial logic of selective preservation extends even to Christian sites. Crusader-era churches, built during the European occupation of Palestine (1099–1187 CE) and in the surviving Crusader enclaves until 1291 CE, continue to receive protection because they fit the European-centered narrative, while Palestinian Christian heritage, beginning with early Christianity and continuing through Byzantine, Islamic, Crusader, and Ottoman eras, is institutionally marginalized and legally excluded.

In his book The Byzantine–Islamic Transition in Palestine, Israeli archaeologist Gideon Avni—widely regarded as relatively objective compared to many of his peers—acknowledged that many sites previously labeled as "Roman" or "Byzantine" were, in fact, Islamic. As Avni wrote, “Sites inhabited in the eighth century were frequently labelled Byzantine rather than Early Islamic. The refining of dating criteria for pottery types has paved the way for a major redating of survey finds and a correction of the flawed picture of settlement density in Early Islamic times.”

His findings contradicted the long-standing Zionist claim that Muslims destroyed civilization in Palestine; instead, Avni demonstrated that Islamic rule brought continuity and development rather than collapse, noting that “the coming of Islam had no direct effect on settlement patterns and material culture of the local population. The change in settlement, stemming from internal processes rather than from external political powers, culminated gradually during the early Islamic period.”

Dr. Ghattas Sayej, a Palestinian archeologist, has documented this pattern of selective interpretation in multiple publications. In Palestinian Archaeology: Knowledge, Awareness, and Cultural Heritage (2010), he noted that "Archaeology has become a field of political struggle in Palestine, where interpretation and presentation of the past are shaped by modern political needs." He elaborated that "The Israeli occupation has politicized archaeological activities in the Palestinian territories by emphasizing biblical periods while ignoring other important historical phases."

This selective approach has concrete effects on heritage preservation. As Sayej explained, "Selective archaeological exploration focusing on certain periods and ignoring others has contributed to the marginalization of large parts of Palestine's cultural heritage."

Echoing these sentiments, Dr. Hamdan Taha, former Director-General of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, emphasized that Palestinian archaeology remains "archaeology under occupation." In his contribution to A New Critical Approach to the History of Palestine (2019), he further argued that "The practice of archaeology in Palestine can be seen as a struggle to protect cultural heritage against the marginalization and erasure of non-Israeli narratives, affirming the Palestinian people's connection to their land across historical periods." Excavation thus becomes an act of resistance—recovering evidence of a multilayered past that defies simplistic religious myths.

Fraud and Forgery

When selective interpretation and institutional manipulation proved insufficient, a more direct approach emerged: outright fraud. Specific artifacts stand as documented examples of deliberate forgery—concrete evidence of how archaeology was manipulated to support biblical entitlement claims.

The Ivory Pomegranate—allegedly from Solomon's Temple and inscribed "Holy to the Priests of the House of God"—was exposed as a forgery in 2005 when microscopic examination revealed modern tool marks beneath the artificially aged surface.

Before this revelation, the artifact had been celebrated as extraordinary evidence of biblical claims. It was claimed to have adorned the High Priest's scepter, potentially proving the existence of Solomon's Temple. The Israel Exploration Journal definitively labeled it a fraud, stating, "The inscription was inscribed on the pomegranate after it had already been broken in ancient times... The conclusion, therefore, is that [the] inscription must be a recent one, very cleverly executed... revealing the true character of the inscription as a sophisticated recent forgery."

The Israel Museum had already purchased it for $550,000 and presented it as the only relic from Solomon's Temple ever discovered. By the time it was debunked, the "discovery" had already strengthened Israeli claims to Palestinian neighborhoods like Silwan and Sheikh Jarrah by "proving" ancient Jewish presence in specific areas targeted for settlement expansion.

The James Ossuary, a small limestone burial box supposedly bearing the inscription "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus," became the center of a major forgery scandal in 2003. Forensic analysis by international experts revealed manipulation of the artifact.

Conservator Jacques Neguer of the Israel Antiquities Authority stated unequivocally, "The ossuary is authentic. Its inscription is a forgery. All the various scratches on the ossuary are coated in the original patina, and only the inscription and its immediate surroundings are coated with an artificial 'patina'-like material of round crystalline granules."

This analysis showed how precisely the forgery had been executed: an authentic ancient ossuary had been altered with a modern inscription, then coated with artificial patina. Geological testing confirmed that the oxygen isotope ratios in the inscription's patina could not have formed naturally in Jerusalem's climate, indicating fabrication using chalk and water to create a false appearance of antiquity.

Similarly, the Jehoash Tablet, claiming to document temple repairs, contained modern chemical compounds in its "ancient" patina and Hebrew grammatical errors impossible in authentic ancient writing. Epigrapher Avigdor Horowitz wrote in the Israel Exploration Journal (2004),"The Jehoash inscription appears to be a combination of elements collected from various sources and pasted together... All the elements together clearly prove that the text is a forgery."

The scientific evidence was equally damning. Geochemist Avner Ayalon's analysis concluded, "Patina of such an isotope composition was probably created from a mixture of materials and water heated to a temperature that does not exist in our area... Therefore, I conclude that the patina in the Jehoash inscription is forged."

Despite these red flags, scholars from Tel Aviv University initially authenticated it, lending academic credibility to annexation campaigns in Jerusalem.

This pattern—fabricate, publicize, colonize, and only later admit the fraud—reveals the direct relationship between archaeological forgeries and territorial control. The timing of these revelations matters: by the time the truth emerged, physical reality had already been altered.

Settlements were established, land seized, and policies implemented based on the fabricated narrative, all bolstered by financial and political support from evangelical Christian groups in the United States who saw these claims as biblical validation.

As Israeli historian Shlomo Sand observes in The Invention of the Land of Israel (2012), "Lack of authentic historical evidence does not prevent nationalist mythologies from establishing themselves. On the contrary, it sometimes compels their creators to invest even more energy in invention."

These forgeries represent not isolated incidents but the most extreme manifestation of a systematic approach that spans from selective interpretation to physical displacement to outright fabrication. Excavations and heritage projects often precede or accompany land seizures and settlement expansion under the guise of science and tourism.

Despite ongoing documentation by Palestinian archaeologists—a form of resistance that preserves historical truth against a machinery of fabrication—the colonial project continues. When history refused to provide the necessary validation for territorial claims, the response was the ultimate colonial action: if archaeology couldn't uncover ancient Israel, then Israel would be manufactured and imposed on the land—artifact by artifact, law by law, myth by myth.

Genetics and the Invention of Identity

“I believe neither in the past existence of a Jewish people, exiled from its land, nor in the premise that the Jews are originally descended from the ancient land of Judea.”

—Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Land of Israel (2012)

As the archaeological account of ancient Jewish kingdoms began to collapse under scientific scrutiny, Zionism turned to a new kind of claim—one rooted not in stones, but in blood. If the land could not prove ancient Israel's presence, perhaps DNA could. The question was no longer just where Israel had been, but who the Israelites were—and who their descendants might be.

Zionism advanced a new mythology: that modern Jews—particularly Ashkenazi Jews—carried the genetic code of ancient Hebrews. Behind this scientific terminology lurked racial theory dressed as heritage, eugenics presented as birthright.

If Jews constituted a "biological lineage," then Palestinian dispossession could be rebranded not as theft but as genetic inheritance. But like the archaeological claim before it, the genetic argument collapsed under scrutiny.

In his trilogy of works—The Invention of the Jewish People (2008), The Invention of the Land of Israel (2012), and How I Stopped Being a Jew (2013)—Shlomo Sand dismantled the core assumptions of Jewish ethnonational identity. Jewishness, he argued, is not a biological essence but a political construct, shaped by conversion, migration, and myth.

"The people known in the world as Jews (as distinct from today's Jewish Israelis) have never been, and are still not, a people or a nation," Sand asserted. "Jews have little in common with each other. They had no common 'ethnic' lineage owing to the high level of conversion in antiquity... 'Jewish People' is a political construct, an invention."

"Most Ashkenazi Jews," he contended, "were not descended from ancient Israelites, but rather from various groups that adopted the Jewish religion in different regions and at different times.”

Sand's critique built upon earlier work by Arthur Koestler, whose 1976 book The Thirteenth Tribe popularized the Khazar hypothesis. "These Jews did not migrate from the Jordan but from the Volga," Koestler stated plainly. "Not from Canaan, but from the Caucasus.”

He maintained that "[The Jewish faith] transformed the Jews of the Diaspora into a pseudo-nation … held together loosely by a system of traditional beliefs based on racial and historical premises which turn out to be illusory." His conclusions directly challenged the foundational myth of a people returning to their ancestral homeland.

Koestler noted that scholarly avoidance of the Khazar hypothesis was not due to scientific doubt but political convenience. "The far-reaching implications of this hypothesis may explain the great caution exercised by historians in approaching this subject—if they do not avoid it altogether," he wrote, "with the obvious intent to avoid upsetting believers in the dogma of the Chosen Race." Such strategic silence preserves a narrative of exclusive ancestral connection that legitimizes colonial claims.

The Khazar theory had even earlier roots in Israeli scholarship. In the introduction to his Hebrew monograph Khazaria: History of a Jewish Kingdom in Europe (1951), Israeli historian A.N. Poliak advanced the hypothesis that a majority of Ashkenazi Jews stemmed from Khazar converts. "The descendants of this settlement," he wrote, "constitute now the large majority of world Jewry"—including those who remained in Eastern Europe, those who emigrated to the U.S. and other countries, and those who went to Israel.

Even Itzhak Ben-Zvi, Israel's second president, acknowledged that Khazars were among the ancestors of early Jewish communities in Eastern Europe.

Egyptian geographer Gamal Hamdan had reached similar conclusions through historical and anthropological analysis. In his 1967 study The Jews: Anthropology, he wrote, "The contemporary Jews are a new people, alien to the original Semitic stock, different in race, in blood, and in history." Zionism, he argued, was "not a religious return, nor a return of sons to their homeland, but a colonial conquest by strangers, executed through invasion, aggression, and sustained by imperialism."

He insisted that Palestinians—not incoming settlers—were the land's true indigenous people. Modern genetics has since validated his assessment.

It's worth noting that critics dismiss Koestler's thesis since it predated modern DNA analysis and was politically motivated in an attempt to challenge racial definitions of Jewish identity that he believed underpinned anti-Semitic ideology. While based on limited historical evidence available at the time, subsequent genome-wide studies have neither fully confirmed nor conclusively refuted the extent of Khazar ancestry among Ashkenazi Jews.

What modern genetics has established, however, is something far more significant: the deep ancestral connection of Palestinians to the land.

Genetic studies consistently show that today's Palestinians have the strongest DNA connections to the region's ancient inhabitants. As geneticist Nathan Pearson of the New York Genome Center explained in his TEDx Boston talk in 2021, Palestinians today have the closest DNA match to Bronze Age Canaanites who lived in the region circa 1700–2500 BCE. This assessment is supported by multiple peer-reviewed studies.

A 2017 study in The American Journal of Human Genetics found that "the overlap between the Bronze Age and present-day Levantines suggests a degree of genetic continuity in the region." The researchers sequenced five Bronze Age genomes from ancient Canaan (in Sidon, present-day Lebanon) and found that DNA from Bronze Age Canaanites was clearly identifiable in the genomes of people living in Bilad Al-Sham (Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine) today, supporting a direct line of genetic descent.

More significantly, a 2020 genome-wide analysis by Agranat-Tamir et al. examined dozens of Middle Bronze Age remains (2100–1500 BCE) across Palestine and surrounding areas. The study reported that Palestinians derive approximately 81–87% of their ancestry from populations of that period, commonly identified as Bronze Age Canaanites.

The remaining ancestry reflects minor admixture from later periods: approximately 8–12% from an ancient East African-related source and about 5–10% from Bronze Age-era Europeans. Notably, the researchers found that Palestinians retain a higher proportion of this ancient Eastern Mediterranean ancestry than Jewish groups with long diaspora histories.

Claims that Palestinians are largely recent Arab immigrants are directly contradicted by this genetic data. The researchers explicitly noted that “Modern-day Arabic-speaking Levantine populations, such as Jordanians, Palestinians, and Syrians, inherited a large proportion of their ancestry from the Bronze Age Canaanite-related population” (Agranat-Tamir et al.,Cell, 2020) and that later migrations—including the 7th-century Arab expansion—“contributed only modestly to the gene pool.”

The evidence instead shows continuous habitation of the region for over 3,700 years, establishing Palestinians as direct descendants of the land's ancient inhabitants.

Even if the genetic claims about Jewish ancestry were true—which the evidence does not support—they would still fail as a moral pretext for displacement. The use of genetics to validate claims of historical ownership reduces complex questions of justice, sovereignty, and human rights to a crude biological determinism. It suggests that rights to land are inherited through blood rather than established through documented historical continuity, legal frameworks, or democratic principles.

If archaeology couldn't locate "Ancient Israel," and genetics couldn't preserve it, what remains is not evidence but a doctrine of supremacy. As we've seen with the archaeological claims examined earlier, historical evidence has been systematically distorted to serve political ends.

"The story of the Khazar Empire," Koestler concluded, "begins to look like the most cruel hoax which history has ever perpetrated." Cruel not only for what it hides—but for what it has enabled.

No amount of DNA can legitimize dispossession.

What began as a theological claim was recast as a biological one. The genetic mythology wasn't built in isolation. It emerged alongside—and reinforced—another constructed concept: "Ancient Israel" itself.

The Invention of "Ancient Israel"

Biblical scholar Philip Davies went beyond critiquing archaeological methodologies to address a more fundamental question: What if "Ancient Israel" itself was a narrative invention rather than a historical reality? Building on the collapse of both archaeological and genetic claims, Davies argued in his groundbreaking work In Search of "Ancient Israel" (1992) that "as a literary construct, Israel is no more and no less than what the writers have made it." What modern nationalism mistook for historical fact was actually a complex conceptual fabrication.

Challenging mainstream biblical scholars who treated ancient texts as historical records, Davies was unequivocal: "The 'Israel' of the biblical literature is, at least for the most part, quite obviously not an historical entity at all. This much can be deduced from the very scholarly writings that talk about it as if it were."

For Davies, the concept of a biologically defined Israel—traced through genes or patrilineal descent—dangerously reduces identity to blood lineage. In Memories of Ancient Israel (2008), he warned that basing identity on genealogy effectively "erases" the actual diversity and complexity of human communities. Within this framework, everything that doesn't fit the narrative—conversion, diaspora, linguistic and cultural adaptation—is treated not as history but as deviation from a purified ideal.

This scholarly critique directly undermines the foundation of modern ethno-national land claims. The mythology creates intellectual space to exclude Palestinians—not because they were absent from the land, but because they are positioned as not belonging to it in the "right" way.

In contrast, Palestinian people embody centuries of continuous presence, documented in official records. Palestinian geographer Salman Abu Sitta has meticulously cataloged pre-1948 land ownership patterns through Ottoman and British Mandate archives. His Atlas of Palestine (2004) provides precise documentation of Palestinian villages, property boundaries, and agricultural holdings through official deeds and tax records before dispossession. These archives directly contradict the narrative of "a land without people."

Shlomo Sand further contested this territorial conception. "The term 'Land of Israel' was a later Christian and rabbinical invention that was theological, and by no means political in nature," he observed. He emphasized that "in no text or archaeological finding do we find the term 'Land of Israel' used to refer to a defined geographic region." The concept was not inherited but retrofitted: "Only in the early twentieth century, after years in the Protestant melting pot, was the theological concept of 'Land of Israel' finally converted and refined into a clearly geo-national concept. Settlement Zionism borrowed the term… in part to displace the term 'Palestine.'"

Sand explained, "My main goal is to deconstruct the concept of the Jewish 'historical right' to the Land of Israel and its associated nationalist narratives, whose only purpose was to establish moral legitimacy for the appropriation of territory."

If David and Solomon's kingdom exists only in biblical texts, then Zionism's historical foundation disintegrates with it—not that archaeological evidence would make ethnic cleansing any less abhorrent.

Whether David and Solomon were "local tribal leaders" instead of grand kings, as most archaeologists have agreed, or altogether something else, the conclusion remains the same. The fable rebrands occupation as return, apartheid as revival, and colonial theft as inheritance.

This fabrication of history serves strategic purposes within a broader colonial framework. As Gamal Hamdan articulated in his 1968 work The Strategy of Colonization and Liberation, "Global colonialism, hand in hand with world Zionism, created this illegitimate entity to serve as a military outpost, a strategic bridgehead, and an economic agent... tearing apart the Arab homeland and draining its resources permanently."

If you were to study the history of Palestine from ancient times until today, without blindly accepting the biblical version of history, what would you find?

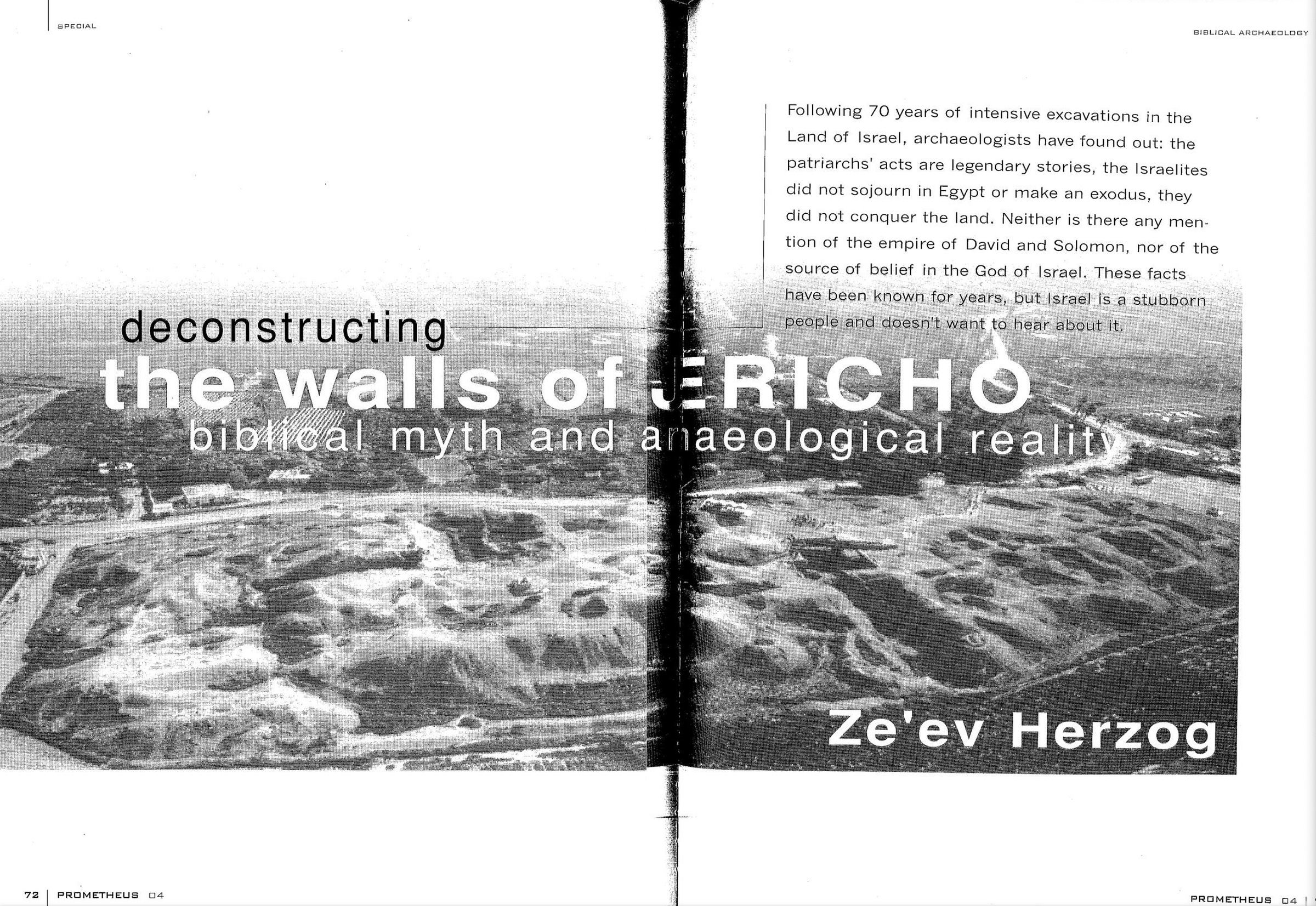

In 1999, Israeli archaeologist Ze'ev Herzog—professor at Tel Aviv University and director of the Institute of Archaeology—published a groundbreaking article in Haaretz titled Deconstructing the Walls of Jericho. His conclusions were definitive: "Following 70 years of intense excavation in the land of Israel, archaeologists have found out: The patriarchs’ acts are legendary stories, the Israelites did not sojourn in Egypt or make an exodus, they did not conquer the land. Neither is there any mention of the empire of David and Solomon."

The article continued with more specifics: "The Israelites were never in Egypt, they did not wander in the desert, they did not conquer the land in a military campaign, and they did not pass it on to the 12 tribes of Israel. Perhaps even harder to accept is that the united monarchy of David and Solomon, described in the Bible as a regional power, was at best a small tribal kingdom."

This wasn't a contrarian position or the view of an outlier. As Herzog stated, "Those interested in this topic have known these facts for years, but Israel is a stubborn nation that does not want to hear about it." The scholarly consensus had fundamentally shifted: "Most of those who work in the interconnected fields of the Bible, archaeology, and Jewish history—and who once entered the field searching for evidence to confirm the biblical story—now agree that the historical events related to the emergence of the Jewish people are radically different from what that story says."

And there's the crux. The historical events are radically different from what that story says.

If the Zionist-messianic storyline is not historical fact, what becomes of using it as such?

A political weapon?

A biblical deed to land?