Scofield’s Bible and the American Embrace of Zionism

How should we understand U.S. presidents and senators competing to outbid one another in loyalty to Israel? And what does it mean when the most powerful politicians on earth reach for Scripture—not as private belief, but as public justification for a foreign state and a colonial project?

The conventional explanations are familiar: strategic interests, military positioning, regional leverage, oil, domestic lobbying. All of this shapes policy; none of it explains the fervor. What requires explanation is the transformation of Israel from ally into sacred cause, from strategy into theology—an attachment that persists even when interests are strained, even when law is inverted, even when Palestinian life is treated as expendable.

The name of that transformation is Christian Zionism: a messianic conviction that history must culminate in Jewish settlement of Palestine and control of Jerusalem as preparation for Christ’s Second Coming. In this reading, history is not a field of human struggle and responsibility; it is a timetable. Palestine is not a living society; it is a stage. And the Palestinians—who disrupt the story by existing—are pushed out of view, or treated as irrelevant.

They are removed from history and from place—including Palestinian Christians whose continuity in the land stretches back two millennia, long before Zionism, and long before the American politicians who invoke Christianity while endorsing their dispossession. A theology that claims Christ’s authority thus produces, in practice, a moral blankness toward those who have lived where Christ lived—whose survival is treated, within the prophecy scheme, as a problem to be managed.

To make this work, Christianity’s moral hierarchy must be inverted. Jesus’ teachings—love your neighbor, blessed are the peacemakers—are subordinated to stories of tribal warfare and ethnic conquest in the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible. Verses from Genesis and Deuteronomy are pulled from context and reassembled into a modern program: exclusive land rights, permanent entitlement, sanctioned dispossession. The ethical becomes decorative; the territorial becomes binding. What results is not faith as moral discipline, but faith as authorization.

This conviction did not begin with Jewish political Zionism; it anticipated it by nearly a century. Long before most Jews embraced the idea of a nation-state in Palestine, British and American Protestants imagined it, theorized it, and lobbied for it—often with a certainty that exceeded that of the people they claimed to be restoring. Its earliest and most fervent advocates were not Jews, many of whom viewed these ideas with suspicion or outright hostility, but Protestant Christians who saw “restoration” as part of God’s prophetic design.

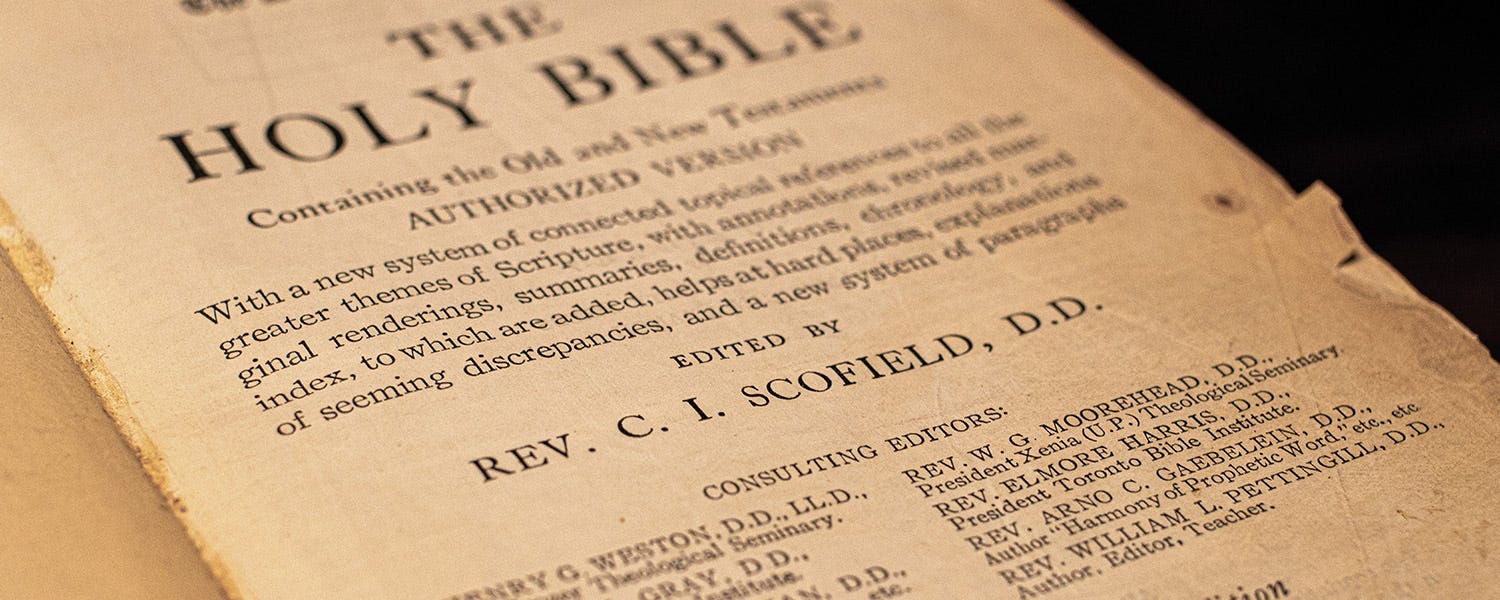

The decisive vehicle for mass dissemination was Cyrus Scofield’s 1909 Scofield Reference Bible, which placed his study notes beside the King James text—printed as if co-equal with Scripture, so that interpretation was absorbed as revelation. Scofield’s framework taught generations of believers how to see Palestine: as a divine title deed, and as a test of obedience.

Central to that framework is the claim that Jewish “return” to Palestine constitutes a divine mandate. From there the logic hardens. If settlement is prophecy, then opposition becomes rebellion against God; criticism becomes sacrilege; political judgment becomes spiritual transgression. A settler-colonial project acquires the protection of the sacred.

More than 60 million American evangelicals have absorbed this theology. It now functions as durable moral infrastructure for unconditional U.S. support—support that shields Israel from accountability while Palestinians are subjected to genocide, ethnic cleansing, siege, forced displacement, and systematic domination. What presents itself in Washington as faith is, on the ground, a way of making conquest look like obedience, and making the victim’s demand for rights look like an interruption of “God’s plan.”

The System of Dispensations

Christian Zionism did not begin with Scofield’s 1909 Bible. Its roots stretch back to the 16th-century Protestant Reformation, when Martin Luther unsettled traditional Christian teaching.

While Catholic and Orthodox traditions held that Christ had fulfilled God’s Old Testament promises, Protestantism restored the Old Testament to unexpected centrality. These traditions had understood the Old Testament as prophecy fulfilled in Christ; Protestants came to treat it as an unfinished covenant with the Jewish people.

Over time, this emphasis transformed how Old Testament promises were read. What earlier Christians understood as spiritual metaphor, later Protestants—especially Puritans and their successors—interpreted as literal territorial claims. American Puritans imagined themselves as a “new Israel” and North America as their “promised land,” using biblical language to justify the extermination and expulsion of Indigenous peoples.

They developed a political theology of ethnic cleansing that drew its vision of racial and ethnic superiority from the land and conquest stories of the Hebrew Bible—especially the Book of Joshua and the texts on Israelite origins that demand the subjugation and destruction of other peoples. The same interpretive logic would later be applied to Palestine, turning ancient scripture into modern entitlement to the land.

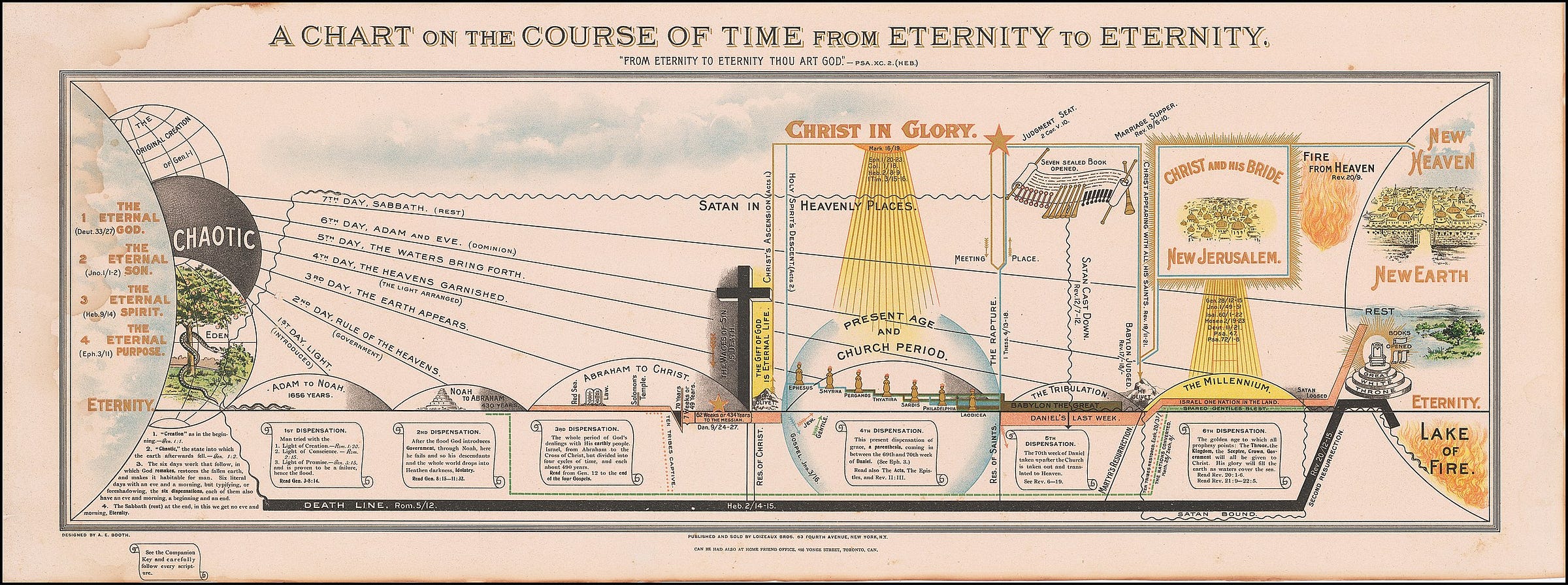

This literalist reading of Old Testament promises found its most systematic expression in dispensationalism. The key to understanding the worldview Scofield built is this interpretive system, which reads the Bible as a series of distinct eras, or “dispensations,” in which God relates to humanity in different ways and assigns specific responsibilities.

Scofield popularized a system that divided history into seven eras. These eras function like a series of contracts between God and humanity—each with its own rules, blessings, and consequences if broken. When humanity fails to keep its side of the contract, God moves on to the next dispensation. God has separate plans for Israel (the Jewish people) and the Church (Christian believers).

According to this view, God’s promises to Israel—the land, sovereignty, and a restored kingdom—were suspended when the Jewish people rejected Jesus as the Messiah. A new dispensation, the “Church Age,” began, understood as a temporary interruption or “parenthesis” in history. In other words, history itself is on hold until God restores Israel. The Church operates on a separate track from the Jewish people until, in this theology, God resumes the original Israel-centered plan.

While dispensationalists believe we are still in the Church Age, Israel’s founding in 1948 was hailed as unmistakable prophetic proof that God’s plan for Israel was reactivating. The milestone was incomplete, however. For evangelicals shaped by Scofield’s teaching, statehood was only the first step. Full prophetic fulfillment requires not only the land’s restoration but also Jewish control of Jerusalem, the construction of the Third Temple, and—ultimately—the conversion of the Jewish people to Christianity.

These prerequisites set the stage for what dispensationalists believe comes next. The Rapture arrives first—when born-again Christians are suddenly taken from Earth to meet Jesus in the air. This is followed by the Tribulation—seven years of global chaos under the Antichrist.

During this period, the Third Temple is constructed in Jerusalem (on the Haram Al-Sharif, where the Al-Aqsa Mosque now stands). Some Jews accept Jesus as the Messiah, while the vast majority who refuse face slaughter. The Tribulation culminates in the Battle of Armageddon and the Second Coming, when Christ returns to defeat the Antichrist’s armies and establish his thousand-year reign from Jerusalem.

This elaborate prophetic fantasy—reading like an apocalyptic thriller—shapes the foreign policy of the world’s most powerful country. In this belief system, supporting Israel is obedience to God; opposing it is defiance of God. For its adherents, this is not politics but a sacred duty, carried out through campaign donations, lobbying, foreign aid, and war.

The Grifter Who Rewrote Scripture

Scofield did not invent dispensationalism; he followed John Nelson Darby, the 19th-century British preacher who first divided the Bible into “dispensations” and insisted on separating the Church and Israel as two distinct peoples of God. Scofield built on Darby’s work, and with wealthy backers willing to fund publication, created the distribution machine that carried dispensationalism into millions of American homes.

Beneath his religious credentials, however, Scofield was a grifter. He abandoned his wife and two daughters, reinvented himself repeatedly, and left behind a trail of fraud and broken trusts. In the late 1870s, he was implicated in fraudulent schemes in St. Louis and even jailed for forgery before his sudden “conversion” in 1879. Shortly thereafter, he relocated to Texas, attached himself to a well-connected evangelical network, and secured a pastor position—a meteoric transformation from conman to church leader.

There he preached Darby’s dispensationalism, cultivated wealthy patrons who bankrolled his ministry, and built the platform that would launch his Reference Bible. That platform—and the networks behind it—would soon link Scofield directly to the centers of imperial power in New York and London.

Scofield, Oxford, and the Balfour Moment

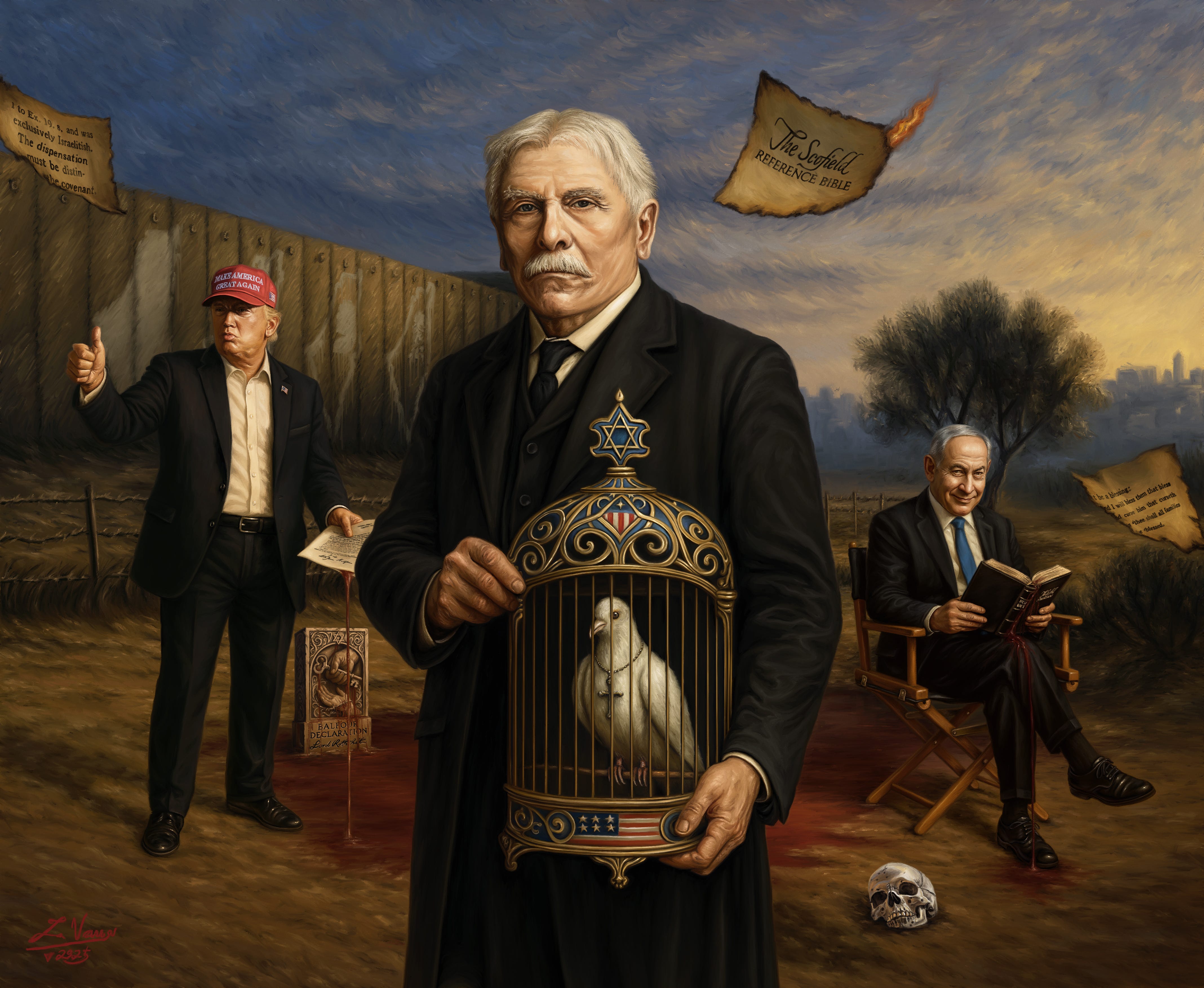

Joseph Canfield’s 1988 biography, The Incredible Scofield and His Book, documents what happened next. By the early 1900s, Scofield’s fortunes shifted dramatically. He was introduced into the Lotos Club—an exclusive New York gentlemen’s club for political and financial elites—by Samuel Untermeyer, a Jewish lawyer and outspoken Zionist advocate with ties to the Rothschild network. Untermeyer’s backing gave Scofield access to circles of money and influence he could never have entered alone.

For Untermeyer, the value was strategic: harnessing Christian support for Zionist aims by presenting them as biblical imperatives. Zionism required the backing of Christian imperial powers to succeed, making Scofield’s evangelical reach invaluable to the political project. Untermeyer’s connections linked Scofield to Zionist-financial circles, including the Rothschilds, and through them to the imperial and Zionist networks that would author the Balfour Declaration.

At the same time, Scofield found another ally in London. In 1908, during a trip there, he met Henry Frowde, Oxford University Press’s London director and a member of the Exclusive Brethren, followers of Darby’s dispensationalism. Frowde took up the project immediately, and in 1909 the press published The Scofield Reference Bible.

For a fringe preacher with a checkered past, the endorsement of Oxford was extraordinary. It gave his notes legitimacy they never could have gained on their own. As the first widely distributed, systematically annotated Bible in English since the Geneva Bible of the 1560s, it reached millions and carried dispensationalism far beyond the small circles where Darby had sown it. Oxford’s name had backed his framework since 1909, giving his interpretations credibility during the years Britain was preparing what would become the Balfour Declaration.

In 1917, Oxford University Press issued a revised edition of The Scofield Reference Bible. Ten months later, the Balfour Declaration pledged British support for a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, addressed to Lord Walter Rothschild. The 1909 edition had already separated Israel and the Church into two distinct peoples and warned that nations would be blessed or cursed depending on how they treated Israel. But the 1917 revision went further, adding blunt notes that “Israel is to be restored to the land” and that “Palestine is promised to the descendants of Abraham.”

These additions corresponded neatly with Balfour’s pledge, giving the impression that the Bible itself had always taught Jewish return to Palestine. In reality, it was Scofield’s commentary distorting the text to serve a political agenda. As Britain embraced Zionist aims, millions of American evangelicals were being taught through his notes that these events fulfilled prophecy. His commentary reframed imperial policy as divine will, putting Darby’s prophecy charts into plain notes in the margins of the most trusted Bible in the English-speaking world. Religion and empire were now aligned.

1967: When Prophecy Seemed Fulfilled

Scofield lived to see this initial alignment between religion and empire but died in 1921, decades before its full implications would become apparent.

In 1967, Oxford issued The New Scofield Reference Bible to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the 1917 edition, a modernized version that refreshed his notes for a new generation. Just months later, Israel captured East Jerusalem and the West Bank in the Six-Day War. Until then, Israel had not controlled the core biblical territories—Jerusalem, Hebron, Bethlehem, Jericho, and Nablus. The war changed that overnight.

Once Israel occupied the “land of the Bible,” the logic of biblical promise gained unprecedented momentum. For Jewish Zionists, it strengthened religious Zionist currents that had existed on the margins, emboldening claims that “Judea and Samaria”—the biblical names for the West Bank—had to be reclaimed and settled. For Christian Zionists, the war brought renewed certainty that prophecy was unfolding literally. Scofield’s prophetic scheme looked vindicated: Jewish control of Jerusalem had long been one of his essential steps toward the end times.

The 1967 edition gave Scofield’s system fresh authority, putting his notes back into millions of hands just as world events seemed to confirm them. Through the 1970s and 1980s, evangelical publishing, televangelism, and prophecy conferences flourished, backed by wealthy donors and publishing houses. Israel’s victory and Scofield’s Bible reinforced one another, binding evangelicals more tightly to the belief that modern wars in the region were unfolding according to God’s plan. Long after his death, Scofield’s name still sanctified war, occupation, and the erasure of a people.

From Footnotes to Foreign Policy

The prophetic certainty generated by Israel’s 1967 victory created fertile ground for mass-market prophecy literature. This is not to say all evangelicals embraced reflexive support—dissenting voices existed. But the dominant current, institutionalized through key evangelical leaders, made Christian Zionism a litmus test of evangelical political identity.

Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth (1970) became the decade’s best-selling nonfiction book. Lindsey popularized Scofield’s framework by reading Cold War events into biblical prophecy—casting the Soviet Union, China, and the European Common Market as signs that Christ’s return was imminent. The book’s influence reached beyond evangelical circles when it was adapted into a 1979 film narrated by Orson Welles, demonstrating how deeply Scofield’s system had penetrated American culture.

Televangelists carried dispensational prophecy into mass-market religion, but Jerry Falwell transformed it into political power. The Baptist preacher mobilized millions of evangelicals into Republican politics, declaring that God had given Palestine to the Jews and that America’s duty was to defend Israel at any cost. When Israel bombed Iraq’s nuclear reactor in 1981, Prime Minister Menachem Begin phoned Falwell to help sell the attack to the Christian public—even gifting him a private jet. Falwell obliged, defending Israel’s actions on television and establishing himself as a trusted ally of the Israeli state.

By the 2000s, John Hagee institutionalized what Falwell had politicized. The Texas megachurch pastor founded Christians United for Israel (CUFI) in 2006, creating an evangelical counterpart to AIPAC. Its annual Washington summits turned Scofield’s reinterpretation of Genesis 12:3 into lobbying strategy. The verse—God’s promise to Abraham, “I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse”—was originally about individuals who helped or harmed Abraham personally. Scofield recast it as a warning that modern nations would be blessed or cursed depending on how they treated the modern state of Israel.

This alliance between evangelical fundamentalism and the political establishment shaped U.S. foreign policy through successive administrations. The merging of prophecy with policy meant that Israel could no longer be judged by secular standards—not international law, not human rights norms, not even American strategic interests. Republican and Democratic administrations alike came to treat Christian Zionism as both voter base and justification for unconditional support.

The Culmination

Donald Trump’s first-term decisions—recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in 2017 and relocating the U.S. embassy there—were celebrated by evangelical circles as confirming dispensationalist predictions, demonstrating how completely this belief system had captured policy. His 2019 recognition of Israeli annexation of the occupied Golan Heights further aligned U.S. actions with dispensationalist expectations.

By 2025, this belief system had secured positions at the highest levels of government. Mike Huckabee, appointed U.S. ambassador to Israel, openly frames Israel’s modern state as a fulfillment of biblical destiny, urging U.S. leaders to see Jerusalem as a divinely ordained “title deed” from God to Abraham’s heirs. In one Jerusalem speech, he declared: “We have the opportunity to be representatives not only of our government, but also representatives of Jesus Christ.” He subsequently announced that the U.S. is no longer pursuing a two-state solution, calling the West Bank “Judea and Samaria.”

In his book American Crusade, U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth frames support for Israel as a Christian mission, calling for an “American crusade” in defense of Western civilization. His tattoos incorporate medieval crusader symbols—one reading “Deus Vult” (”God wills it”), the First Crusade’s battle cry—making his religious zealotry publicly visible.

Senators Ted Cruz and Lindsey Graham invoke scriptural logic. In his June 2025 exchange with Tucker Carlson, Cruz grounded his stance in biblical promise, paraphrasing Genesis 12:3 in its Scofield-reinterpreted form: “those who bless Israel will be blessed, and those who curse Israel will be cursed,” and adding, “I’d rather be on the blessing side of things.” At a rally in South Carolina, Graham took the distortion further: “If America pulls the plug on Israel, God will pull the plug on us.”

Emboldened by this dispensationalist consensus, Israeli leadership had become increasingly brazen. Benjamin Netanyahu framed Israeli expansion in explicitly biblical terms. He presented territorial conquest as a “historic and spiritual mission” to secure Greater Israel, invoking scriptural language to describe the occupied West Bank as Israel’s ancient homeland and rejecting the concept of occupation itself. In August 2025, announcing new settlement expansions, he declared this was “not the end—it’s the beginning.”

A month later, in September 2025, Trump and Netanyahu jointly announced a 20-point plan said to end the genocide in Gaza. It began as a 21-point proposal that Trump presented to Arab and Muslim leaders, who welcomed it. According to Arab officials, one point would have barred Israel from annexing the West Bank, but that clause was excluded before the announcement.

The final text requires the Palestinian Authority to complete a reform program “as outlined in President Trump’s peace plan in 2020.” That 2020 “Peace to Prosperity” blueprint contains the key: it requires Palestinians to formally recognize Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people and to forfeit claims to Jerusalem by accepting it as Israel’s sovereign, undivided capital. These are the precise preconditions that Scofield outlined as necessary for Christ’s Second Coming.

Securing these demands brings a millennial pattern to completion. For a thousand years, Western Christian empires have pursued Jerusalem—with shifting theological justifications but consistent imperial methods. Medieval Crusaders sought to establish Christian sovereignty over the holy city. Modern dispensationalist theology requires Jewish sovereignty as a prerequisite for Christ’s return.

The theological frameworks differ, but the perpetrators and methods remain constant: Western Christian empires treating indigenous presence—Muslim and Christian alike—as obstacle to be removed for religious supremacist ends.

Scofield’s interpretation of the Bible resonated with Americans because it mirrored the logic that they had already deployed across their own continent: Indigenous peoples cast as obstacles to God’s plan, land theft framed as divine right, Old Testament language deployed to bless ethnic cleansing. Israeli territorial expansion would provide Jewish control of Jerusalem, which this theology demanded to trigger the end times.

American evangelicals and the Israeli state converged in mutual dependence, each requiring the other’s success. The dispensationalist system supplied the checklist; the shared history of settler colonialism supplied the methods.

What began as notes in a study Bible became the ideological apparatus through which American power justifies the dispossession of the very communities where the faith was born. When American politicians invoke Genesis in defense of Israeli policy, they are not speaking metaphorically. They implement Scofield’s 1909 interpretations with weapons and diplomacy and defend the dispossession as the will of God.

The dispossession this theology justifies extends with particular irony to Palestinian Christians. Communities that trace unbroken lineage to the apostles themselves—in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, Ramallah, Gaza—and that sustained their faith through two millennia of changing empires were erased through the modern Christian Zionist vision. Dispensationalism required the land be emptied of all its indigenous people to make space for a political project conceived in imperial capitals and carried out through decades of occupation, siege, and slaughter.

This was an excellent article and an eye opener, and pretty much demolishes whatever legitimacy the Zionist fascist state derived from distorted scriptural logic.

This text shows how a distorted theology has been turned into a tool to justify the occupation and destruction of a nation. No true faith can be built on the devastation of others’ homes. Palestine is not merely a matter of politics. it is a matter of human conscience.🕊