The Colonial Subcontracting System

Israel and the Palestinian Authority

What does it mean when a colonial power assigns the work of domination to the very people it subjugates? The question is not rhetorical. It goes to the heart of the Palestinian predicament today, and to the elaborate fiction that surrounds what is called the “peace process.” For what has been constructed in Palestine since 1993 is not the foundation of a future state but something far more insidious: a system in which the colonized are made responsible for administering their own subjugation, in which the oppressed are transformed into instruments of the oppressor, and in which the language of self-governance is deployed to mask the deepening of occupation.

The relationship between Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA) exemplifies a logic that students of colonialism will recognize immediately—the logic of indirect rule, of subcontracted domination. The British perfected this system in India and Africa; the French employed it across the Maghreb and in Indochina. Its genius lies in its economy: rather than bearing the full cost and condemnation of direct rule, the colonial power installs a local elite whose interests become bound to the perpetuation of the colonial order itself. Oslo and its economic counterpart, the Paris Protocol, were celebrated in the West as the foundations of Palestinian statehood. But what they produced was statehood’s opposite: a fragmented territory, an economy imprisoned by dependency, and a Palestinian leadership made responsible for policing its own people on Israel’s behalf.

The Oslo Accords

Oslo was not a peace agreement. It was, to call it by its proper name, an instrument of capitulation. Conducted in secret by a handful of PLO officials—none of them lawyers, none of them with maps adequate to the task, none of them, it must be said, with democratic mandate from the Palestinian people—the 1993 accord bypassed not only the Palestinian delegation negotiating in Washington but the entire collective achievement of the First Intifada. That uprising, which shook the Israeli occupation between 1987 and 1993 and forced upon the world a recognition that Palestinians could not simply be ignored or wished away, had earned something precious: the beginning of international acknowledgment that Palestinian national rights were not simply humanitarian concerns but political ones requiring a political solution.

And what did Oslo do with this achievement? It squandered it. In exchange for recognition of the PLO—a recognition that cost Israel nothing and committed it to even less—the Palestinian side received only the promise of “limited self-administration.” Not sovereignty. Not statehood. Not even a commitment that such things might eventually be discussed on terms other than Israel’s. The central questions—the fate of the settlements, the status of Jerusalem, the right of return for the millions of refugees created by 1948—were “deferred,” which is to say they were conceded in advance. For in any negotiation, to defer a question indefinitely while the stronger party consolidates its grip on the disputed territory is not to postpone resolution but to predetermine it.

To implement this arrangement, the accords created the PA as a governing body in the Occupied Territories. Yasser Arafat and the Fatah leadership, returning from their long exile in Tunisia, assumed its helm. Let us be clear about what this meant. The PLO—which had been, whatever its faults, a national liberation movement representing Palestinians everywhere, from the camps of Lebanon to the diaspora of the Americas—was transformed overnight into a local municipal administration under occupation. Edward Said called it at the time a “Palestinian Versailles,” and nothing in the intervening years has proven it to be any different. It was an agreement that exchanged the struggle for liberation for the privileges of authority under continued subjugation.

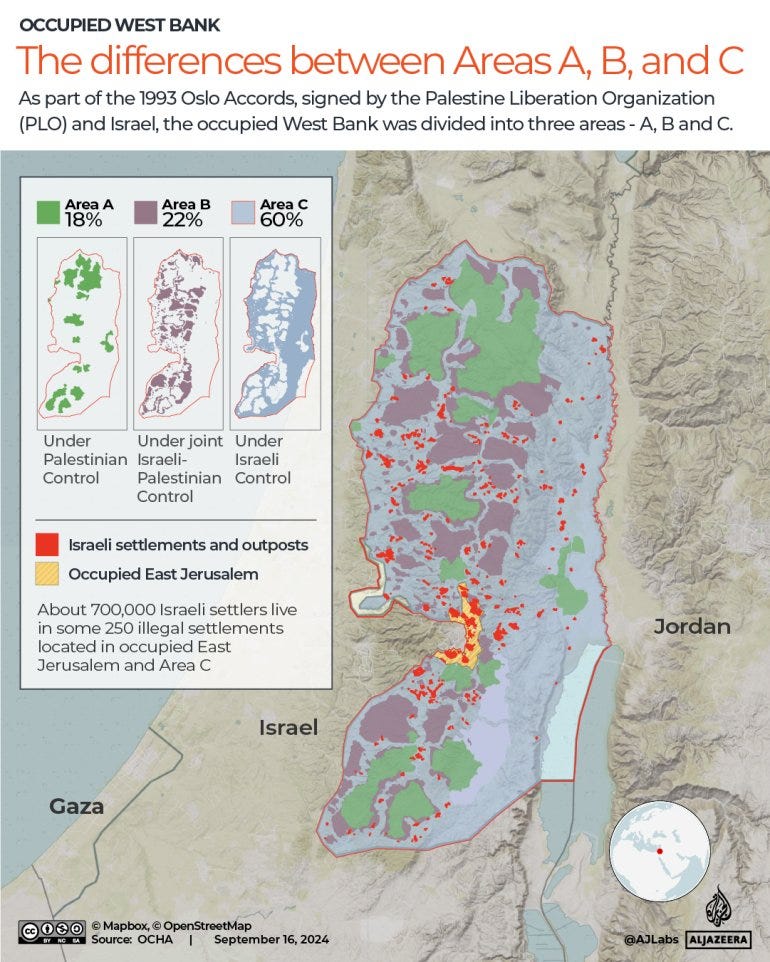

The accords carved the West Bank into Areas A, B, and C—an alphabet soup of fragmentation that confined Palestinian “self-rule” to isolated enclaves comprising just 18% of the territory. Israel retained security control over Area B and complete control over Area C, which constitutes 60% of the West Bank and contains nearly all its natural resources, its aquifers, its arable land. What was announced to the world as Palestinian self-governance was in reality Israeli rule by another name, a system in which settlements expanded, bypass roads multiplied, and Israel tightened its grip on every border, every water source, every road of consequence—while the PA was charged with keeping order among its own dispossessed population.

The fragmentation was not only territorial but psychological, which may in the end prove the deeper wound. By severing communities, by making the simple act of traveling from one Palestinian town to another a gauntlet of checkpoints and permits, Oslo dismantled the collective space necessary for national consciousness and organized resistance. Its system of “security coordination” bound the PA to suppress dissent and pursue resistance members, often in direct alignment with Israeli intelligence priorities.

In Jenin, for example, the PA moved against its own people under the Orwellian banner of “Protect the Homeland”—a demonstration of how thoroughly subcontracting succeeds in turning the colonized into instruments of their own subjugation.

Economic Dependency: The Paris Protocol

If the Oslo Accords constructed the political architecture of subcontracted domination, the Paris Protocol of 1994 erected its economic scaffolding. This agreement, largely ignored by Western commentators eager to celebrate the “peace process,” bound the Palestinian economy to Israel with chains that have only tightened over three decades. It deprived the PA of any meaningful fiscal sovereignty by placing customs duties and value-added taxes on goods destined for Palestinian markets entirely in Israel’s hands.

These revenues—which constitute the bulk of the PA’s operating budget—are “transferred” to the Palestinians only at Israel’s discretion, withheld whenever compliance must be enforced or punishment administered. What was presented as economic coordination has functioned in practice as a system of coercion, turning livelihood itself into an instrument of political control.

In 2024, Israel’s Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich deducted $26 million from Palestinian tax revenues, triggering a financial crisis that left thousands of public-sector workers without full salaries. This was the system’s very logic made manifest—the reduction of autonomy to appearance, the deployment of economic dependency as an instrument of discipline.

Colonial powers have always understood the utility of economic leverage. By controlling livelihoods, they secure compliance; by enriching a small collaborating elite, they create a constituency for the continuation of colonial arrangements; by impoverishing the majority, they breed the despair and disorganization that make resistance difficult.

The Paris Protocol reproduces this pattern in Palestine with remarkable precision. A privileged few—those connected to the PA leadership, those positioned to benefit from the monopolies and import licenses that Oslo’s architects distributed—have prospered even as unemployment, poverty, and hopelessness have spread among the population at large. Far from preparing the ground for sovereignty, the protocol institutionalizes subordination, ensuring that economic freedom, like political freedom, remains structurally unattainable.

For Israel, the arrangement is both cost-effective and politically convenient. By outsourcing civil administration and security to the PA, it avoids the expense and international scrutiny of direct occupation. By controlling revenues through the Paris Protocol, it wields economic dependency as another form of discipline. Meanwhile, settlements expand and the occupation deepens. What appears to foreign observers as progress toward statehood is in fact the refinement of domination—a colonial system made more efficient, more deniable, more permanent.

From the First Intifada to Gaza’s Blockade

The Oslo and Paris accords were framed as the pathway to Palestinian statehood, but they were bookended by two moments that reveal a different trajectory altogether: the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference and the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections. Between them came the Second Intifada, which erupted in 2000 after the collapse of Oslo’s hollow promises and widespread disillusionment with the “peace process.” Understanding what subcontracted occupation has wrought requires tracing this arc.

Madrid was the political fruit of the First Intifada. That uprising—led not by the PLO leadership in Tunis but by Palestinians on the ground, organized through popular committees and sustained by collective sacrifice—forced a global recognition of the Palestinian cause that decades of armed struggle from exile had failed to achieve. For the first time, Israel was compelled to negotiate not from goodwill but because the cost of continued occupation had become intolerable.

But two years later, in Oslo, that achievement was bartered away in secret talks, as Arafat and the Fatah leadership traded the gains of the Intifada for their return from exile, for political authority, for the trappings of governance that the PA would provide. The people who had made the First Intifada were not consulted. The prisoners who had led the uprising remained in Israeli jails.

The Second Intifada, which erupted after Ariel Sharon’s provocative visit to the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in September 2000, expressed in violent form the accumulated frustrations with Fatah’s stewardship—the corruption, the collaboration, the manifest failure to deliver anything resembling liberation. It ended in 2005 under the weight of brutal Israeli repression, followed by Israel’s unilateral withdrawal of settlers and soldiers from Gaza and the dismantlement of its settlements there. But this withdrawal was not a concession; it was a strategic repositioning. Gaza was to become an open-air prison, blockaded from land, sea, and air, its population subjected to collective punishment whenever resistance manifested itself.

The following year, legislative elections were held in the West Bank and Gaza. Widely regarded by international observers as transparent and fair, they produced a decisive victory for Hamas. Thirteen years after the signing of the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian people rendered their verdict on that bargain—a resounding rejection of the PA’s corruption, its complicity, its failure. And how did the self-proclaimed champions of democracy in Washington, Tel Aviv, and European capitals respond? They moved instantly to nullify the result, imposing sanctions on the Hamas-led government, cutting off the funds on which the PA depended for its patronage networks.

Under the supervision of U.S. General Keith Dayton, PA security forces were armed and trained specifically to confront Hamas, escalating internal tensions and fueling the clashes that would tear the Palestinian national movement apart. By 2007, Hamas had taken control of Gaza while Fatah consolidated its rule in the West Bank. The division became permanent, giving Israel the pretext it required to tighten its occupation and impose on Gaza the blockade that persists to this day—a blockade that has reduced two million people to conditions that international observers have repeatedly described as uninhabitable.

The trajectory could not be clearer. What began in Madrid with hard-won recognition of Palestinian rights was reduced in Oslo to subcontracted authority, and by 2006 had fractured into rival administrations in Gaza and the West Bank, each too weak to challenge Israel effectively, each available to be played against the other. At every stage, Israel has exploited these divisions to tighten its grip, treating Palestinian disunity as proof of incapacity for self-rule.

What is offered in place of genuine sovereignty is the appearance of choice—elections held under occupation, negotiations conducted without leverage, the trappings of authority without its substance. And when those choices do not conform to Israel’s terms, they are dismissed outright, with Palestinian division invoked as evidence that there is no “partner for peace.”

The result is a circular logic that entrenches domination—Israel manufactures fragmentation, exploits it to expand control, and then cites it as the reason why peace cannot be achieved.

The Path to Liberation

While Israel profits from this colonial system of subcontracted control, the costs for Palestinians have been devastating. They face the double burden of resisting occupation while overcoming internal divisions that fracture the struggle itself. The political rivalry between Fatah—clinging to its authority and its accommodations with the occupation—and Hamas, which has refused to abandon the language and practice of resistance, has weakened the collective capacity to challenge a system designed to perpetuate itself.

The PA has accommodated itself to the reality of occupation, displacement, and dispossession. It has adopted the vocabulary of its patrons, speaking of “peace” and “security coordination” and “confidence-building measures” when what is required is resistance to an ongoing injustice. Hamas, whatever one thinks of its methods or its ideology, has at least maintained the fundamental position that occupation must be opposed, not managed. These divisions serve Israel’s interests perfectly. As long as Palestinians remain fractured, as long as their leadership is divided between those who administer occupation and those who resist it from impossible circumstances, the system will persist.

Abolishing this proxy system of control is essential—not only for tactical reasons but for the recovery of Palestinian political coherence. The PA’s reliance on Israel, its complicity in preserving a status quo that benefits only the occupier, undermines any broader struggle for justice and self-determination. What is called “reconciliation” under these circumstances is submission misnamed as compromise, where the rhetoric of peace is weaponized to suppress resistance and delegitimize those who refuse to accept permanent subjugation.

Freedom cannot be granted by the colonizer. This is the lesson of every anti-colonial struggle, and Palestinians will not prove an exception to it. What can be said is that neither the devastation of occupation nor the catastrophe presently unfolding in Gaza has broken the determination of those who refuse to accept their fate. Despite siege, bombardment, and scarcity that would have crushed lesser peoples, resistance continues.

The world may fail to recognize their worth. The powerful may dismiss them as terrorists, as obstacles to a “peace” that was never genuinely on offer. The media may ignore their suffering or frame it in ways that obscure the fundamental asymmetry between occupier and occupied. But the struggle belongs to a history far larger than any single moment—the history in which the colonized refuse the roles assigned to them, in which the oppressed decline to manage their own subjugation, in which peoples who were told they did not exist assert their existence in the only terms their oppressors understand.

The Palestinians are not fated to administer their own dispossession. Sooner or later—and the arc of history suggests it is always later than the oppressed would wish and sooner than the oppressor expects—they will dismantle it.

🫡🫡

This is deeply powerful and inspiring. It’s a reminder that true freedom cannot be granted by oppressors, and that resilience and resistance persist even in the face of unimaginable hardship. The determination of the Palestinian people is undeniable. ✊💔